Elephants, American Indians, and the Circus

by LeAnne Howe

My mother collected elephants, bronze, ceramic, silver, large and small urns shaped like elephants, and even a belt with the silver images of marching elephants. After she died in 2003, my brother and I were going through her things and dividing the mementos that we each wanted to keep. I chose her elephant collection. Today the yellow, or gray, or silver elephants of all shapes and sizes rest in various places nooks and crannies in the house that has been passed down from my grandmother, to my mother and now me.

Until I began the research for my novel Mike Kings: An Indian Baseball Story (Aunt Lute Books, 2007) set in Ada, and later research for our new play, Side Show Freaks and Circus Injuns, co-authored with Monique Mojica, I had no idea why my mother was drawn to elephants. But it seems that circuses and elephants loomed large in the minds of American Indians in southeastern Oklahoma, and certainly in my mother’s imagination. Small and intermediate-sized circuses began coming to Ada, Indian Territory, as early as the 1890s. The Ada Weekly News began writing about the circus in Ada in 1904.

photo by LeAnne Howe

When circuses came to Ada, they always parked in Daggs Prairie about six blocks from my grandmother’s house. My mother and my great aunt Euda and their friends would always sneak in the backside of the circus tents and watch the elephant, tiger and bears that were part of the circus acts. Sometime around 1929 my great aunt Euda joined the circus, and she traveled all over the world as a circus performer. Euda was only a few years older than my mother, and the two looked like sisters and remained very close until their deaths.

Enter Sideshow Freaks and Circus Injuns

Over the past seven years I’ve been working with indigenous actress and playwright Monique Mojica, and others on an indigenous research project for our 70-minute play about mounds, mound building and theatrical performance. Both Monique and I had family members that were in the circuses. Our play involves developing new Indigenous performance models based dramaturgically on Indigenous cultural texts: earthworks. Indian Mounds were built by layering different kinds of soils one upon the other. As Indigenous playwrights Monique and I will employ the deep structure of earthworks as dramaturgical models. Our soil layering will be represented in the stories we “layer in the play” with circus acts and our two principle characters, Panther Girl and Invisible Woman. We began our research at mound sites by asking a simple question: How do Natives embody the lands of their origin? To help with our research we talked with tribal elders and residents in Native communities in close proximity to mounds, and we visited mound sites from Canada to Louisiana, and read historical documents.

What we found was that in the 19th and early 20th centuries, modern circuses parked on mound sites. Why mound sites is a little unclear, but one guess is because the sites were ready made for the circus tent. I’ve since wondered if my great aunt Euda had played Indian on any of these mounds sites.

The Western Hemisphere is populated with mounds and earthworks in various ages from the Archaic, Early Woodland, Middle Woodland, and late Woodland/Mississippian periods. In the Southeast some of the great mound cities are Poverty Point (Louisiana), Moundville (Alabama), Nanih Waiya (Mississippi), and Okmulgee (Georgia). Other earthworks known as Hopewell era sites are located across Ohio and the Ohio Valley. At one time, hundreds of thousands of mounds, including embankments, conical mounds, platform mounds, and effigy mounds, dotted Indigenous North America, beginning as early as 4000 BCE. The very name “Turtle Island” connotes a vast effigy mound rising out of the water.

In studying mounds as Indigenous literatures, we asked other questions. Are the earthworks embodied mnemonics aligned with moon and sun rotations to show future generations of Natives when and where to converge at specific sites? Another indication of the return motif. One thing is certain, the circus always returned to Ada to perform for two weeks at a time, as if following in the footsteps of indigenous people who designed “return elements” via cosmic alignments at all these mound sites in Native north America.

photo by LeAnne Howe

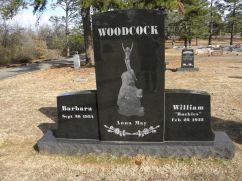

Today at Hugo, Oklahoma, located within the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, is Showmen’s Rest, Circus Cemetery for all the “showmen under God’s big top.” Indeed, it’s a graveyard of circus performers of ages past. You will note the elephant statues that graces the graves of past circus performers. Hugo, the second oldest Choctaw town in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, has been a “popular winter headquarters for traveling circuses, earning the nickname “Circus Town, USA,” according to Hugo’s website.

In finding out so much of the history of the circus that came to town and enticed my family members to join it has been a joy and a sorrow. A joy because they were brave people to uproot themselves. A sorrow because I should have asked more questions when my mom was alive: “Why did you collect elephants, Mama?” In writing this play, I think I’ve found the answer. But I’m sure there is more to the story.

photo by LeAnne Howe

photo by LeAnne Howe

LeAnne Howe is an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. She writes fiction, poetry, screenplays, creative non-fiction, plays and scholarship that primarily deal with American Indian and Native American experiences.

Her first novel Shell Shaker (Aunt Lute Books, 2001) received an American Book Award in 2002 from the Before Columbus Foundation. The novel was a finalist for the 2003 Oklahoma Book Award, and awarded Wordcraft Circle Writer of the Year, 2002. Equinoxes Rouge, the French translation, was the 2004 finalist for Prix Medici Estranger, one of France’s top literary awards. Evidence of Red (Salt Publishing, UK, 2005) won the Oklahoma Book Award for poetry in 2006, and the Wordcraft Circle Award for 2006. Her most recent novel is Miko Kings: An Indian Baseball Story (Aunt Lute Books, 2007). Her latest two books Choctalking On Other Realities (Aunt Lute Books), a memoir, and Seeing Red Pixeled Skins, American Indians and Film (Michigan State University Press), a co-edited anthology of film reviews were both published in 2013. She is the Eidson Distinguished Professor of American Literature in the English Department at the University of Georgia, Athens. She is available for readings and lectures at colleges and universities.

She is now working on an Irish Choctaw Chapbook with Irish poets Doireann Ní Ghríofa and Padraig Kirwan about the 1847 Choctaw gift to the Irish for famine relief.