Máirín Kenny, PhD, is a former teacher, principal and educator who has worked for over thirty years with students and parents from the Irish Traveller community, a recognized indigenous ethnic minority within Ireland. Dr. Kenny is currently an independent scholar and conducts commissioned research on equality, disabilities, ethnicity, racism, and sectarianism in Irish education. Hawk Hopes Blog invited Dr. Kenny to share some perspectives on what it means to be an agent of change within the Irish educational context. Here is what she had to say. —Sorcha Hyland

Who are the “Irish Travellers”?

Irish Travellers have been a distinct group in Irish society since at least the twelfth century. They are Irish, but a recent human genome research project has shown them to have been genetically separate since at least the sixteenth century. And only this year they won recognition in Irish law as an ethnic group—a status they have had since 2000 in Northern Ireland (under UK law). There are ethnic populations all over Europe, similar to the Irish Travellers. It is officially recognized that these peoples are targets of the most virulent racism across Europe. There are Irish and European people who will accept immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers—but not the Travellers, or the Roma.

The Irish Travellers’ economic activities married well with nomadism. They turned their hand to whatever trade or service was required and could cover a territory large enough to survive. They traded in horses and donkeys, they worked as blacksmiths (shoeing horses and donkeys), and tinsmiths (making and mending tin cans, buckets, basins—hence their older name “tinker”, a term that acquired pejorative racist meanings). And in the days before village shops, they hawked— selling small domestic goods such as wool and kitchen utensils. Irish Travellers included all sorts of traders who could provide a range of mobile services to a wider territory than the sedentary working population could feasibly cover. In the twentieth century, they turned to trading in second-hand goods, scrap metal, gardening, etc. But the space for these services has shrunk. And at the same time, they are virtually shunned in the employment market—currently, unemployment among Travellers runs at above 70%.

The question “who are they?” is a good one. It never struck the dominant Irish settled population to ask that question—still less did it strike us to ask the Travellers that question. In the early 1960s, prominent social activists discovered the plight of this group—a population of about 6,000, living on the roadside in miserable tents and wagons, with no services, scant access to health or education services, a life expectancy of 30 years, and an infant mortality rate seven times the national rate. But these leaders, and the government, once stirred to action, assumed that these people were dropouts, perhaps descended from homeless peasantry in Famine times. And the solution was to settle them down, clean them up, and fit them in.

In a negative sense, nomadism also shaped everything. In Ireland (and in the UK and elsewhere), Irish society and social structures (law, housing policy, etc.) have traditionally used nomadism as a tool to destroy the nomad: historically, they were needed but not wanted by local communities. Once the work was done, the Travellers had to move on; and at an official level roadside camping was made illegal. In short, the timing of their movements was dictated by the settled population, and the conditions for dignified nomadism were cut from under them, where they existed at all. Very few of them are now nomadic, and even fewer want to be so.

In a negative sense, nomadism also shaped everything. In Ireland (and in the UK and elsewhere), Irish society and social structures (law, housing policy, etc.) have traditionally used nomadism as a tool to destroy the nomad: historically, they were needed but not wanted by local communities. Once the work was done, the Travellers had to move on; and at an official level roadside camping was made illegal. In short, the timing of their movements was dictated by the settled population, and the conditions for dignified nomadism were cut from under them, where they existed at all. Very few of them are now nomadic, and even fewer want to be so.

But when they try to settle, they are still in the wrong “place”. Housing policies have driven them into standard accommodation (hugely inappropriate and inadequate), and those who move now do so because they can’t find anywhere to live. Everyone wants them to stop travelling, but not to stop it “here”—Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY-ism).

Today, there are perhaps 40,000 Irish Travellers. Theoretically they have access to all the social services, but racism still raises its ugly head to narrow that. They nearly all stay in school until age 15 years, but that is shockingly far below the completion level for the general population—the education system is failing them more than any other sector. Their life expectancy is 11 years below the national average for women, 15 below for men. Infant mortality is over three times the national average. Suicide rates for men are seven times the national rate, and for women 4.5 times the rate.

Why did you choose to work in school provision for Irish Travellers specifically?

When I chose to work with the Irish Travellers I also thought they were at the extreme end of rural disadvantage—so marginalized that they were homeless. I think I quickly realised that was far from the whole story—if it was part of the story at all.

As a teacher, and later principal in a school for Irish Traveller children, and as a sociologist I was very interested in educationally disadvantaged populations. From the get-go, I wanted to work with people who were experiencing marginalization. I wanted to learn more about and with the people who were being forced to operate in the fringes of the Irish public education system.

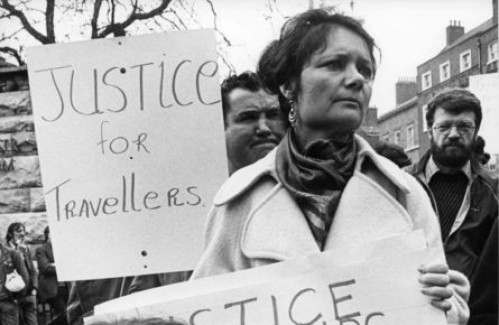

Nan Joyce, Irish Traveller activist and spokeswoman, 1984. Photograph by Eamonn Farrell. Published in http://www.thejournal.ie, March 1, 2017.

What have you learned from your professional experiences both as an educator, a principal and a researcher in relation to Irish Travellers?

It took me a lot of work to really get it that the Irish Travellers are a people with a distinctive identity and approach to life. And one that I have grown to understand and respect hugely. In 1978 I became principal of a school that had been set up entirely for Travellers. Then, the idea didn’t seem as shocking as now! And, I developed an agenda for it—two long-term aims, and once they were achieved, the school should go.

First of all, I argued that like any silenced group, Travellers needed their own space to find their voice, and to read their world, to reclaim their pride, and reflect on their situation—free, for as long as necessary, of the hostile gaze of the oppressor. I think Liégeois (a French specialist on Roma and Travellers in Europe) had a point when he said that the paradox facing Travellers was that they had to enter the house of the oppressor to gain the tools to end their own oppression.

Secondly, I was very concerned with an unspoken notion that I saw at least implicit in education policy towards them– that “Traveller culture” is a euphemism for poverty or deviance. A submerged racism. And among Travellers, there was a mirror-version of that—expressed often in the words “how can Travellers all in together learn anything?” I wanted the school to prove that Traveller culture provided a rich space for a proud and distinct school identity and curriculum, and that Travellers all in together could learn, could go from there to any school of their choice, as good as any child or youth from any other school in the town. In my school, the children could be openly Traveller, and they go on into local secondary (=middle/high) schools, well able to state their case, challenge racism and say why it was wrong. But at the same time, I know that there was a larger structural lesson being learned: the students were Travellers, and were being kept separate.ut at the same time, I know that there was a larger structural lesson being learned: the students were Travellers, and were being kept separate.

However, the mainstream Irish public education system is just not flexible or intuitive enough yet to take in all the different perspectives that ethnicity in Ireland presents. In theory and even in practice, we know where we need to get to. In terms of securing the kind of national and international support necessary to ensure all students, of all ethnicities, have access to fair and culturally appropriate free public education—Ireland– like other European Union member states, like other developing and industrialized and even post-industrialized nations—has a way to go yet. But I think school provision is the wrong place to start.

What has your practice in the field, and your research revealed to you?

The huge thing I have learned – when approaching populations who have been marginalized to the extent that Irish Travellers are –severely disadvantaged, encountering multigenerational cycles of unemployment…the attitude of the dominant education or academic community is often misplaced. The focus tends to be “Let’s get to the children and rescue them first”. I have learned that it can’t work this way. That this way of remediating a human rights problem, particularly involving children and youth from ethnic minorities, does not work. In my experience here you can’t work with the children if you don’t work with the community that envelops the children. In a human rights framework. If the parents are empowered and enabled, if we make a space where they can explore possibilities beyond what has been allowed or offered to them before– then they—the parents, the grandparents, the family members, the guardians and caregivers from within the marginalized population—will make sure the children get the best that they can get.

Traveller boys in Dublin, Ireland, 1980. Photograph by Brian Palm.

Our focus needs to shift to not just parental access to education, or parental rights in education, but to creating meaningful and culturally responsive parent-professional interactions where parent-driven professional learning and development can occur. As opposed to teachers working solely with children from populations where they have no prior knowledge or understanding of that population as a living ethnic minority, an evolving culture. Or where they have no professional preparation in critical and culturally reflexive and responsive practices to inquire and learn about the cultures their students and families bring to the classroom.

How are Irish Travellers impacted by other international realities, such as state, EU- and UN-driven incentives around inclusive and special education, if at all?

Irish Traveller girl, 1965. Photograph by Alen MacWeeney (b. 1939) from his publication Irish Travellers: Tinkers No More (2007).

In the 1960’s, once it was discovered that Irish Traveller children and youth were not going to school on any kind of a consistent basis, activists campaigned to have resources available to them within the special education system (the only avenue to augmented resources available at the time). This was a strategic move, tempting for well-intentioned educational activists. The objective was to intensively up-skill these children, prior to “absorbing” them in the “normal” classes . But the children didn’t move on. Not until the inclusion movement of the 90’s. And then— (beware of what you pray for, you might get it)—in 2007, the Irish Department of Education produced Notes towards a Traveller Education Strategy. Combining the inclusion principle with the need to cut back expenditure, the Department axed all home-school and resource-teaching provision for Travellers. In future, Traveller children would access resources on the basis of need, not identity. How to separate the good from the bad in that statement!?

As regards special education generally, since the 1970’s Ireland has become increasingly influenced by international frameworks of thinking across Europe and more globally as inclusive education, in all its variants, has become the name of the game. This too can be a risky thing. The ideal of inclusive education can only be realised if, in the transition from special provision, the child in question loses nothing of the resources and supports they received in that provision. Truly inclusive education, in any context and of any variant, has got to be more expensive. It must entail additional services and supports and professional training that enable the modern, “inclusive” classroom to be truly universal. At a policy level across EU and in Ireland – we continue to see merely locational inclusion – the placement of children with special needs and/or with generational obstacles to education access all thrown together, in the name of inclusive education. This is not building inclusion. This is in fact worse than exclusion. This is a cost-saver.

How do you distinguish between good versus bad, or even ‘not so good’ practices of inclusive education, in the contexts you focus on?

Locational inclusion is merely a body-count. Are they in the same room? All day? If yes—job done. But real inclusion is making sure every child that is in the room owns the place, belongs. They must feel enabled to operate to the best of their ability within that setting. For example, true inclusion would enable children to access a space where they could remove themselves from a larger group, read, or relax, or sail their boat within the majority classroom. Inclusion must be elastic and modular. It must have a continuum of provisions. All students, including Irish Traveller students, need supports. They all need spaces to draw their breath. All children have the right to the tools and the supports necessary to enable them, in their bodies and with their unique strengths and challenges, systemic or biological, to find their way within the majority classroom. That is inclusion.

How do you describe the educational system in Ireland in general terms?

The general education system in Ireland is too rigid. We should have a continuum of provision so our students, from all ethnicities, with all levels of forms of learning and ability, can operate wherever they need to be to speed ahead or go at their own pace with their own lives. So, if a child needs a lot of physical therapy within the given school-day, they can have this provision within the system and no obstacles in terms of when or how they re-join their peers or class cohort. Our hidden curriculum, not unlike that in the United States, is definitely one of competition and survival of the fittest. At the end of the day you come out of education with or without the piece of paper you need to get into third level (institutes of higher education). There is an undertow separating people for the purposes of economic stratification, that informs the Irish and it seems, most Western public education systems.

Teachers in the Irish public school system are academically bright, highly qualified, and respected in the community with a very strong tradition of successful unionization. The primary (in U.S. terms “elementary”) school teaching force is trained to teach all students aged 4-12 years, not bifurcated into “general” or “special”. But they are almost all middle class, white, and indigenous. Given the rapidly growing ethnic diversity in Irish society, and the movement to inclusive education provision (under-resourced of course), Ireland needs a more diverse teaching force, and substantial investment in relevant, high-quality initial teacher education and continuing professional development.

Where else might the Irish public education continue to evolve, in your opinion?

In the Irish public education system, we need to continue to grow in parent-teacher communication and partnerships. Both on a whole school basis and to face the challenges that arise as new shifts and unexpected realities emerge from our societies at large. The huge increase in diversity in Irish society, over the course of my own career and especially over the last 15 years points to the impact that forced migration, including economic migration, has had on Irish society. Along with that front-end challenge, the system of educational organization has to become more flexible, it has to move beyond its own hidden curriculum and narrow cultural focus.

It is good to see the education partnership growing, where parents, teachers and children become partners in the whole education process. The move towards inclusive education is very good, but it is grossly under-funded. Parents and caregivers in Ireland are no longer sitting on the sidelines. They have become much more vocal.

How did your doctoral work inform your understanding of educational practice and educational leadership in the Irish system?

I did my doctorate in sociology in Trinity College Dublin while I was still teaching. I was a graduate student, a school principal, and a classroom teacher simultaneously. I went into research to try to figure out what were we missing in what Travellers themselves had to say about education, and in how they used language to describe what they were “not”. I love research and I love trying to understand what people say and how that relates to policy.

Equality, equity and the belief that everyone has the right to have access to whatever supports they need to do the best they can informed my position. We should never allow a structural block to limit a person’s potential. That structural block might be a door that isn’t wide enough to allow someone on wheels or using alternative mobility supports to enter, or a system that does not reach out to where people really are. I see no value in just saying “We are very inclusive. So you can now come to us”. If people have centuries of experience behind them, where they know, are told, and experience that they are not welcome – it is not enough for a state institution to just change its mind and say “come on in”. The system must go out to the people, it must reach out to the communities that have experienced marginalization, discrimination, exclusion, oppression – and learn how to include them.

From the designers of educational curricula all the way up to the policy maker– we must know who we have omitted/are omitting, we must reach out to them, learn about them, inform the system how to fully recognize and include them (Bryan, 2010) – to ever proclaim “nothing about us without us”, or “all means all”, or “everyone is welcome”. This is their right.

Otherwise we just sound patronizing.

Bio

Máirín Kenny, PhD, is a former teacher, principal and educator who has worked extensively and for over thirty years with students and parents from the Irish Traveller community, a recognized indigenous ethnic minority within Ireland. She is currently an independent scholar. Dr. Kenny has conducted commissioned research on equality, disabilities, ethnicity, racism, and sectarianism in Irish education. She co-edited Traveller, Nomadic and Migrant Education (Routledge, 2009) with Patrick Danaher (University of Southern Queensland). She authored a chapter for Education in Indigenous, Nomadic and Travelling Communities (Eds: R. Griffin and P. MacÉinrí. Bloomsbury, 2014); and co-authored a chapter for Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (Eds: AK Schulte & B Walker-Gibbs. Springer, 2016). Most recently, she co-authored a book chapter on special education in the Republic of Ireland for The Praeger International Handbook of Special Education (Eds: M. Wehmeyer & J. Patton, 2017) with Dr. Thérèse McPhillips (St. Patrick’s College, Ireland), Sorcha Hyland (Department of Special Education, University of Kansas) and Dr. Michael Shevlin (Trinity College Dublin, Ireland).

References

Bryan, A., (2010). Corporate multiculturalism, diversity management, and positive interculturalism in Irish schools and society. Irish Educational Studies, 29(3), pp. 253-269. http://doras.dcu.ie/21480/

Liégeois, J. P. (1994). Roma, Gypsies, Travellers. Council of Europe.

Watson, D., Kenny, O., & McGinnity, F. (2017). A Social Portrait of Travellers in Ireland. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin, Ireland.