Home » Advocacy

Category Archives: Advocacy

From War to Peace and Education for all… Rwanda

When most people think of Rwanda, they cannot help but remember the country’s tragic history. In a period of 100 days in 1994, over a million Tutsi were killed in what is considered one of the worst genocides of the 20th century. Today, however, Rwanda is better thought of as a country of warm, welcoming people and diverse natural beauty. Known as the land of a thousand hills, the mountainous central African country is located just 75 miles south of the equator and boasts dense, equatorial forests in the northwest and a tropical savannah in the east, with five volcanoes, 23 lakes and numerous rivers (Government of Rwanda, 2020).

One of the unfortunate consequences of the violence during the 1994 genocide was an increased prevalence of people with disabilities in Rwanda, a fact that has helped to shape a strong disability movement within the country (Njelesani et al., 2018). The government of Rwanda is now committed to protecting the rights of persons with disabilities, especially the right to education. This is reflected in the Special Needs and Inclusive Education Policy (2018), which counts among its priorities the equitable access to education for students with special educational needs in mainstream and special schools.

The promise of providing an equitable education to students with disabilities is not simple. The 2014 Rwandan school census estimated that around 24,862 children with disabilities were attending preschool, primary and lower secondary schools. This represents less than one-percent of all students enrolled at that time (UNICEF / Education Development Trust, 2016). According to the 2011 World Health Organization’s World Report on Disability, approximately 5.1% of children between birth and 14 years of age live with some type of disability. It is likely, therefore, that many children attending school in Rwanda have unidentified disabilities. This is further supported by the fact that it is often teachers who fill out the school census and the identification of children with disabilities tends to focus on those readily noticeable impairments.

To help Rwandan teachers meet the needs of all their students, including those who may have special educational needs but who have not been formally identified as having disabilities, Inclusive Development Partners (IDP) has partnered with the Soma Umenye project (funded by USAID and led by Chemonics International) on an inclusive education pilot.

In the period from January to March, 2020, the team provided training and follow-up support to 25 first grade teachers, head teachers, and sector education inspectors, on Universal Design For Learning (UDL) strategies that have been specifically considered for use in the unique context of Rwandan schools.

Why UDL?

UDL is based on the premise that by offering learners flexibility in the way information is presented (multiple means of representation), the way learners engage with materials (multiple means of engagement), and the ways learners express their understanding (multiple means of action and expression), teachers can better prepare for the variability in their students that is natural in human development (Meyer et al., 2014). A further advantage of UDL is that it does not rely upon specific technologies or resources. This is important for Rwandan schools, where many classrooms do not always have consistent access to electricity and material resources are limited to those objects teachers can readily find in their environment.

What does UDL look like in the Rwandan classroom?

Engagement: To keep students engaged, teachers tried a number of different strategies, including using a visual schedule at the beginning of class to help students know the expectations for the lesson, singing the alphabet song while clapping or pointing at the letters they have already learned, and implementing classroom rewards wherein the teacher would dance or sing for the students when they successfully completed their work.

Representation: To provide multiple means of representation, teachers sometimes made models of letters out of sticks or folded grasses that students could touch, brought in household objects to act out the events of a story (such as dirty vegetables and a bucket to demonstrate washing), or made a game of mixed syllable cards for students to build words out of.

Action/Expression: In order to provide students with flexibility when demonstrating their understanding, teachers would ask students to walk around the room and point to objects that began with a target letter sound, match words with their pictures on the chalkboard, or work in pairs to share ideas.

How do these activities differ from good teaching?

Many of the UDL strategies introduced during this project may seem like “just good teaching”. Traditional teaching in Rwanda, however, relies heavily on a model in which students, seated in rows, follow along in unison as a teacher writes on a chalkboard. This is a legacy that the Soma Umenye project has attempted to address more generally, through the provision of scripted lesson plans that build in evidence-based literacy strategies and student-centered methods. Adding to this innovation, the UDL strategies observed in the early months of the pilot project in Rwanda represent a new way of thinking about how students engage with learning. A major emphasis across these strategies is the increased participation of students in the learning process, whether it be through more hands-on learning opportunities or small groups where the students support one another. As one teacher put it:

“Before UDL, I didn’t know what to do with these students (students with disabilities); we just brought them in, but we didn’t ask them questions or anything. Now I know I can support these students. UDL has made all learners our friends.”

References

Njelesani, J., Siegel, J., & Ullrich, E. (2018). Realization of the rights of persons with disabilities in Rwanda. PLoS ONE, 13(5), E0196347.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. T. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Republic of Rwanda. (2020). Welcome to Rwanda. Republic of Rwanda. https://www.gov.rw/

Republic of Rwanda. (2018). Revised special needs and inclusive education policy. Ministry of Education. https://mineduc.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf_files/SNE_Policy__4.10.2018.pdf

UNICEF / Education Development Trust (2016). A study on children with disabilities and their right to education: Republic of Rwanda. https://www.unicef.org/esaro/Rwanda-children-with-disabilities-UNICEF-EDT-2016.pdf

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability 2011. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int

Our Author…

Nicholas Hoekstra is a visually impaired martial artist who somehow found himself pursuing a PhD in special education. After several years working in international development in Ecuador, as an advisor on inclusion, and then with the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Accessible Books Consortium, Nick became interested in strategies for inclusive education in low-income and low-resource environments. He has worked on projects in over 20 developing and least developed countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Strollin’ with Nolan

By Sean Joseph Smith

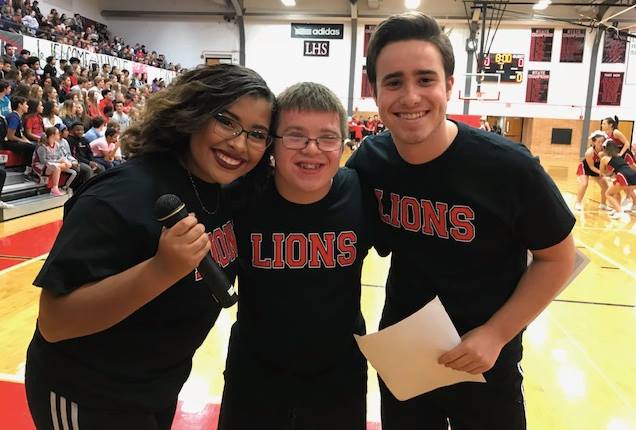

Nolan and I were asked to write this blog to share a little about Nolan and a local social media hit, Strollin’ with Nolan. Strollin’ with Nolan began as a series of short videos that Nolan and Brad Stoll–Lawrence High School Baseball Coach and Adaptive Physical Education (APE) teacher– took at various locations around the school. Brad posted each video on the Chesty Lions Twitter Feed.

It took only a couple of Strollin’ Tweets and the series began to receive tremendous feedback with followers wanting more. Brad started to receive text messages if he happened to skip a regular stream of installments!

Nolan and his APE and Baseball Coach, Brad Stoll at Lawrence High School, Lawrence, KS.

Before long, the posts grew with a regular following. Brad’s posts garnered likes from all over with the LHS Baseball twitter feed receiving more attention than the average tweet. Overall, the videos were a hit, Brad and Nolan have shared a number of stories over the years, and with him being part of the baseball team (Baseball Manager), the videos have fostered a more supportive environment as a member of the team.

As I reflected on this blog though and the story to share about Strollin’ with Nolan, I kept coming back to the fact that the videos go beyond a simple social media post. You see, video has played an important part in Nolan’s life and it represents so much in Nolan’s educational experience. Now, I am not talking so much about the technology tool that video can and often represents. Yes, video is cool and video modeling and similar interventions are effective. But for Nolan, video has offered meaningful entry into the general education classroom, the curriculum, and the overall expectations. Let me explain.

“Nolan and I”

When Nolan transitioned from 3-5 services to the early primary grades, inclusion wasn’t a slam dunk. Instead, extensive time in a resource room or para led instruction was recommended if not required. Through a number of discussions, pre-planning, and working with some excellent educators, Nolan received the supports needed to make general education inclusion for grades K-2 work. This involved regular meetings with his general and special education teachers. My wife and I also spent a fair amount of time in the general education classroom volunteering. Being there provided a chance to see Nolan in action, understand the class expectations, assist the teachers (thereby developing a relationship with him/her), and get to know his peers. During evenings and weekends, we pre-taught some of the major concepts and worked to prepare Nolan for the next day or week. Yes, a team approach during a time when schools are often open to including students with an intellectual disability in the general education classroom, is needed.

With the elementary grades upon us, the team approach continued to be critical. Yet, expectations grew. For a limited reader who had difficulty in writing, school was problematic for Nolan. The pressure to spend more time in the resources room and less time with typically developing peers mounted. We were being reminded that Nolan was an outlier and the services we were advocating for, the decisions for placement, and the supports that were needed went beyond typical services. Yet, everything we sought aligned with the provisions to the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) and so we continued to advocate.

By 3rd grade, our advocacy centered around technology. Technology to provide access to content, tools to demonstrate what he knew, and technology to make the learning experience more effective as well as efficient, particularly when you considered the brief school day and the increasingly shorter school year. In the end, applications like word prediction, graphic organizers, digital books (with text-to-speech support), and of course, video made a HUGE difference in Nolan’s educational experience. For example, word prediction allowed him to type in a letter and receive a list of words, he could then listen to the words and determine which would be best for a sentence. The other technologies were helpful but video was the equalizer. Video was used to create social stories, starring Nolan and his classmates, where he would illustrate the appropriate behavioral and social interactions expected in the classroom, hallway, cafeteria, and playgrounds. In place of a class presentation, Nolan created videos where additional time, practice, and editing allowed him to convey what he wanted to share. By the time he transitioned to middle school, videos were part of most every school day.

Nolan connecting with a true celebrity at the National Down syndrome Congress Annual Convention, Ricki Sabai.

Like any transition, moving to Middle School proved to be a challenge. Though we planned ahead, a number of the teachers weren’t sure what to make of Nolan. Again, there was a special room for the Nolans of the world. Inclusion meant gym, a few electives, and lunch. It certainly didn’t include all academic subjects, band, theater, and other electives. Fortunately, we had an accomplished videographer. With no time for oral reports or class presentations, Nolan was expected to complete the worksheet or related written assignment. Within three weeks, teachers questioned his placement and ability. Realizing failure meant segregation, Nolan put together a brief video presentation on the early American explorers. He sent the video via email on a Friday and by Tuesday his social studies teacher was singing his praises. She went from a primary skeptic to his number one advocate. For the remainder of his middle school years, the separate room was not mentioned again.

Nolan as keynote speaker at Rhinestones & Rodeo Art Auction and Dance with Kate Dougherty. This event hosted by Down Country, its biggest fundraiser of the year.Down Country helps raise awareness and help individuals with disabilities.

By High School, Lawrence Public Schools had adopted a blended learning instructional model. Video was commonplace as a means to represent ideas and support the student in demonstrating what they knew. In other words, Nolan and his video projects were cool! They had also come full circle. While Brad Stoll was adding more and more Strollin’ with Nolan videos, Nolan was beginning to create his own. As a journalism student, he pitched the idea of creating a series of Strollin’ with Nolan interviews for the Yearbook/Journalism website. He would invite staff or students to be interviewed, develop the questions, storyboard the interview, conduct the interview, and the edit the production in order to share with others. His first featured a para he liked to see:

Soon, he was developing audio and video episodes where he continued to interview members of the Lawrence High School community which would be featured on the LHS Budget Online,

Nolan and his fellow classmates Emceeing Pack the House (for Winter Sports) at Lawrence High School. Inclusion at work with thanks to the STUCO Advisor (Mrs. Lauxman) and his peers who are accepting, welcoming, and empowering. We are blessed and Thankful!

Today, Strollin’ with Nolan continues! Strollin’ with Nolan Interview.

Brad and Nolan post periodic updates on the LHS Baseball Twitter feed and Nolan develops material for the LHS Budget Online. But it extends beyond the social media. Nolan’s videos require a level of organization, idea generation, scripting, and overall storyboarding – a process he leads. The video requires speech fluency and effective articulation. Where else then to receive speech and language support from his Speech and Language Pathologist? She is with him twice a week working with the script and practicing to ensure competency and independence.

A labor of love for Nolan that serves as a tool for meaningful access to the general education classroom, social inclusion, and school notoriety where Coach Stoll often refers to Nolan as the Mayor of Lawrence. Why? Everyone seems to know Nolan.

Adaptive Sporting and Recreational Programs Empower Disability Acceptance

By Timothy E. Hornik, LMSW, CATIS, US Army Veteran and Founder of Blind Not Alone.Tim is a disability and Veterans advocate pursuing a PhD in Therapeutic Sciences through the University of Kansas Medical Center. He adheres to Dr. Ed Canda’s concept of transilience, or going beyond who you were before to become someone new. He has earned various military and civilian recognitions for his service.

Mr. Hornik earned military and civilian recognition for service. During his military experience, he received the Meritorious Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, the Purple Heart for injuries sustained, Army Accommodation Medal with Valor for actions in combat, campaign ribbons for service in Iraq and Korea, Combat Action Badge, and many other awards. During his civilian life, he received the University of Kansas (KU) MSW Margo Award for clinical practice, the KU Wounded Warrior Scholarship for his PhD pursuits, inducted into the inaugural UW La Crosse ROTC Hall of Fame, and nominated by UW La Crosse for the US Army ROTC Hall of Fame.

As we flip through social media feeds it is common to hit upon anything from a shared post on some fitness app, like Straba, to “liking” a friend’s running race results These posts may motivate us to remain physically active or inspire us to establish health and wellness goals (Teodoro & Naaman, 2013). Our timelines and feeds lead us to conclude that the society generating our online experiences clearly cares about physical fitness. Unfortunately, the National Institute of Health recently reported otherwise. In the last decade one out of three American adults and 13% of American adolescents achieved an average body mass index (BMI) classification of either overweight or obese (Ng et al., 2014).

For individuals with disabilities, the chances of being overweight or obese are even greater. In 2010, The Center for Disease Control reported 57% more adults and 84% more adolescents with disabilities were overweight and/or more obese than their peers

Factors such as access to quality nutrition, financial and social resources to engage in physical fitness-related activities, secondary effects of medications or conditions, and access to suitable equipment and programs, directly impact these elevated rates (Jaarsma, Dijkstra, Geertzen, & Dekker, 2014; Warburton, Nicol, & Bredin, 2006).

Dr. Robert Chen, left, and Tim Hornik appear pleased following their portion of the blinded veteran relay at the California International Marathon.

However, by understanding how to achieve fitness goals, individuals with disabilities may reverse national trends. In a study of older adults, moderate to vigorous physical activities three times a week lowered their mortality rates by 22% (Hupin et al., 2015).

Children who participated in a group aerobic and strength training program for 60 minutes twice a week achieved fitness goals established by the 2010 President’s Fitness Test for their age groups (Fragala-Pinkham, Haley, Rabin, & Kharasch, 2005). For adults, research pinpointing precise strategies or fitness requirements vary based on an individual’s disability. Community and group programs tend to do more than just empower one to reach their fitness goals, they more importantly aid in the process of accepting a disability or adopting a positive disability identity (Lai, Young, Bickel, Motl, & Rimmer, 2017; Lundberg, Taniguchi, McCormick, & Tibbs, 2011; Ponchillia, Ponchillia, & Strause, 2002).

The impact of fitness goals goes beyond health and wellness. It alters self-perception. Consider an individual who has just lost their sight. It’s common for people in this position to feel suddenly secluded. The simple act of going for a run resides largely outside of their abilities without accommodations and supports. No cane technique affords one the chance to truly hit a moderate to vigorous running pace and cycling independently remains elusive—at least for the time being. The solution requires a community approach. Blind Running or cycling quickly becomes a team sport through sighted guides and tandem captains. An individual’s results range from the achievement of fitness goals, to a sense of belonging, to engagement with community, to empowerment in establishing new independent living goals (Ponchillia, Ponchillia, & Strause, 2002)

The sense of positive effects of being a part of something greater than oneself in achieving a previously impossible goal echoes my feelings generated during my time in the US Army before losing my sight — and in every race or event I’ve participated in since then. My sight loss stems from injuries sustained during combat operations in Iraq. The Warrior culture places a significant value on one’s ability to demonstrate individual physical prowess during fitness tests and to developing a sense of cohesion, improved morale, and esprit de corps through group activities.

Throughout my military service, my fitness goals pushed me to exceed minimum requirements and obtain the maximum score possible. Early in my career, I managed to easily achieve this, earning the respect of those under my leadership and generating a high level of self-confidence. These feelings of accomplishment came crashing down after I lost my sight and could no longer independently run, cycle, or do a host of other activities.

During my rehabilitation process, the Department of Veterans Affairs, Army Wounded Warrior Program, and friends and family contributed to developing my disability identity. Initially I rejected outright all attempts to integrate tools and skills which brought any attention to my blindness. The only exception involved assistive technologies for computers. This would align with my love for computers and an understanding of the role they would play in my remaining time in the Army. At no point during this period did anyone attempt to assess my capacity for setting goals in adaptive sporting or recreational programs.

Nearly a decade after being injured, Richard Hunter, a blind Marine, drew my attention to adaptive sports through his events for the visually impaired division of the California International Marathon. While I participated in a couple of events for disabled Veterans, none of them truly demonstrated the power of adaptive sports to foster life changing dynamics between peers, volunteers, and community supporters. It mattered not whether one crushed the marathon with a two and a half hour time or if they putzed through a leg on a relay team like I did. We all celebrated, regardless of our differences, together. For the first time, I truly felt proud to be blind.

It does not matter whether one establishes a goal to win their division or to simply participate. I continue to feel this way throughout any of the events I attend. When Dr. Mike Reynolds and I competed in the 204 mile Dirty Kanza gravel race, we constantly found ourselves surrounded by other riders asking about tandem riding. The funniest part is that no one realized I was blind until they saw me crossing the stage with Dr. Reynolds with my white cane to mount the first-place podium for the tandem class. Likewise, my sighted running guide, Chris Benjamin and I, spent much time talking with each other and fellow participants during the Kansas City Marathon and the Trolley Run.

VA Awards $8M in Adaptive Sports Program Grants to Aid Disabled Veterans. Image taken from U.S Department of Veterans Affairs.

It is high time for adaptive sporting programs to cease to be viewed as hobbies or remedial recreational programs for individuals with disabilities. Rather, rehabilitation plans and individual educational plans need to incorporate fitness and adaptive sporting measures. This would benefit individuals with disabilities by providing the tools needed to combat obesity, promote disability acceptance (Lundberg et al., 2011), forge lasting community bonds (Zabriskie, Lundberg, & Groff, 2005), and increase employability (Lastuka & Cottingham, 2016).

References

Fragala-Pinkham, M. A., Haley, S. M., Rabin, J., & Kharasch, V. S. (2005). A fitness program for children with disabilities. Physical therapy, 85(11), 1182-1200.

Hupin, D., Roche, F., Gremeaux, V., Chatard, J.-C., Oriol, M., Gaspoz, J.-M., . . . Edouard, P. (2015). Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged≥ 60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2014-094306.

Jaarsma, E., Dijkstra, P., Geertzen, J., & Dekker, R. (2014). Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 24(6), 871-881.

Lai, B., Young, H.-J., Bickel, C. S., Motl, R. W., & Rimmer, J. H. (2017). Current trends in exercise intervention research, technology, and behavioral change strategies for people with disabilities: A scoping review. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 96(10), 748-761.

Lastuka, A., & Cottingham, M. (2016). The effect of adaptive sports on employment among people with disabilities. Disability and rehabilitation, 38(8), 742-748.

Lundberg, N. R., Taniguchi, S., McCormick, B. P., & Tibbs, C. (2011). Identity negotiating: Redefining stigmatized identities through adaptive sports and recreation participation among individuals with a disability. Journal of Leisure Research, 43(2), 205.

Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., . . . Abera, S. F. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The lancet, 384(9945), 766-781.

Ponchillia, P., Ponchillia, S., & Strause, B. (2002). Athletes with visual impairments: Attributes and sports participation. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness (JVIB), 96(04).

Teodoro, R., & Naaman, M. (2013). Fitter with Twitter: Understanding Personal Health and Fitness Activity in Social Media. ICWSM, 2013, 611-620.

Warburton, D. E., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian medical association journal, 174(6), 801-809.

Zabriskie, R. B., Lundberg, N. R., & Groff, D. G. (2005). Quality of life and identity: The benefits of a community-based therapeutic recreation and adaptive sports program. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 39(3), 176.

Strengths Based Inclusive

All doctoral students and faculty in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas participate in specializations. The six specializations include the Strengths Based and Inclusive Approaches to the Education of Adolescents with Extensive and Pervasive Support Needs sequence of which I co-lead. I suspect that our specialization has the longest program sequence name in the entire field of education and it doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. Because several of us have had a hard time getting the full name correct when asked, we’ve started calling it Strengths Based Inclusive for short.

KU Department of Special Education website

Leaving the length of the name aside for a moment, there are probably many people outside of the field of special education, and perhaps some inside as well, who might be curious about our focus on “strengths”. After all, our doctoral sequence is intended to prepare scholars whose future work concerns children and adults with disability diagnoses that are consistent with intellectual disability and related developmental disabilities. Isn’t that population different from the general population because of their deficits?

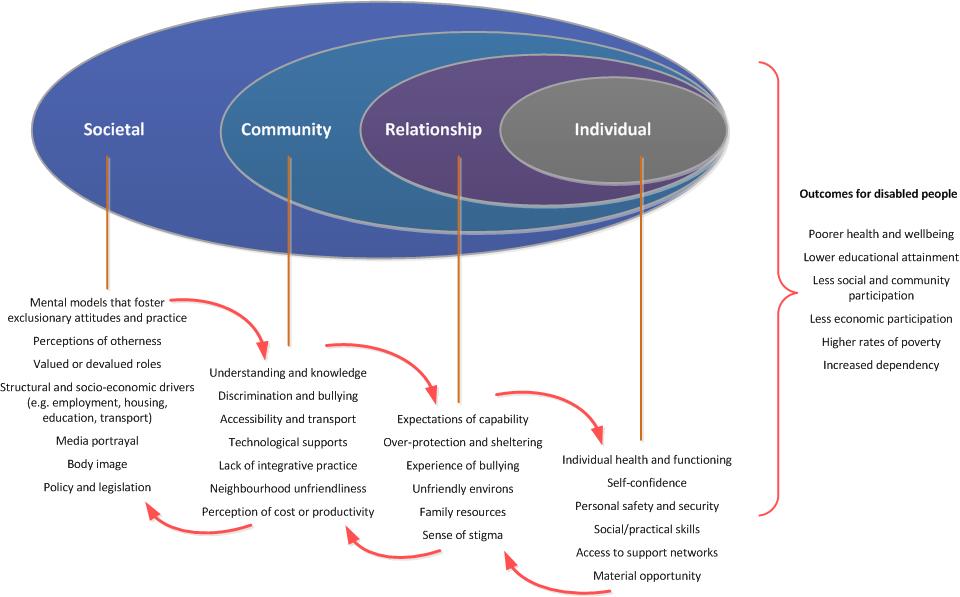

The definitions that are used for diagnoses of disability clearly suggest that evidence of a deficit is a distinguishing characteristic. For example, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), intellectual disability is “a disorder with onset during the developmental period that includes both intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits in conceptual, social, and practical domains” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 33). This deficit-based definition and approach to understanding people with disabilities is consistent with what has traditionally been known as the medical model of disability.

Identifying deficits within a person can be useful to the extent that deficits can be prevented or remediated. Certainly, preventing neurological impairment and teaching people useful skills are worthwhile endeavors. However, the downside to the medical model becomes apparent in instances where a condition cannot be prevented (i.e., the central nervous system is already formed) and achievement gaps cannot be fully remediated, even with the very best instruction.

Illustration by Pete Gamlen.

When viewed through a medical model lens, a condition that cannot be fixed is understood to be a chronic pathology. An implication of such a conceptualization is to focus professional efforts on caring for people in specialized settings, much like people who are physically ill being provided care in a hospital. Pathologizing and medicalizing disability has historically resulted in restricting people’s opportunities to participate as full citizens in society.

An alternative to the medical model is a social-ecological model to understanding disability, where disability is understood in terms of the fit between a person’s competence and the demands of community environments. Understanding people this way focuses professional efforts on modifying the context in which people function. It is important to point out that a social-ecological conceptualization does not call for denying that people with disabilities experience limitations in personal competency. Their limitations in competency, however, are not their most salient characteristic. According to a social-ecological conceptualization, the most important difference between people with disabilities and the general population is that people with disabilities need extra support to successfully participate in daily life activities in community settings. Educators and other human service professionals are called to prioritize time and energy on (a) making environments and activities more accessible and welcoming, and (b) identifying and arranging personalized supports so that a person can successfully participate in culturally valued settings to afford access to rich life experiences.

An alternative to the medical model is a social-ecological model to understanding disability, where disability is understood in terms of the fit between a person’s competence and the demands of community environments. Understanding people this way focuses professional efforts on modifying the context in which people function. It is important to point out that a social-ecological conceptualization does not call for denying that people with disabilities experience limitations in personal competency. Their limitations in competency, however, are not their most salient characteristic. According to a social-ecological conceptualization, the most important difference between people with disabilities and the general population is that people with disabilities need extra support to successfully participate in daily life activities in community settings. Educators and other human service professionals are called to prioritize time and energy on (a) making environments and activities more accessible and welcoming, and (b) identifying and arranging personalized supports so that a person can successfully participate in culturally valued settings to afford access to rich life experiences.

Zahra Al Dhamin, Saudi Arabian sculptor. Photograph by Gadsen-Hayton. BBC Online blog review of exhibition Disabled People at Work by Kathleen Hawkins, June, 2014.

So, in terms of the real world, what does this changing conceptualization of disability really mean? I know a young man whose life experiences provide a good example of the power of a strengths-based, supports oriented, and inclusive approach to working with people with disabilities. For the past five years this young man has been employed as an office worker in one of the world’s largest insurance companies. His job involves sorting and delivering mail and running an array of office machines, while often being pulled away from his own duties to help others in the office who are in a pinch. From a deficit-based perspective, an observer could point out that it took him longer to learn his job tasks compared to others whom his company might have hired, and he has continued to require more direction and coaching on the job than most other employees. He might never had been hired had the focus been placed solely on these challenges.

Instead, his strengths were taken into consideration and he has proven to be an excellent, long-term employee. Although he could not learn job tasks as quickly as others, this was not a weakness that kept him out of the job market. Rather, his commitment to learning helped him master the duties his job required, and once he learned them he learned them well. The fact that he needed more direction and coaching than others did not prove to be an insurmountable obstacle to job success. Rather, his job required someone who was willing to follow directions from others, and it was important to have someone who could be counted on to do job assignments as directed. His eagerness to help others and his flexible disposition were strengths that served him well in a job that required him to step away from his normal duties and assist others who found themselves in a time crunch. Perhaps his most important talents were his cheerfulness and ability to bring out the best qualities in others. These personal strengths had a positive effect on the office climate, which enhanced everyone’s productivity and motivation.

The Two Fridas (1939) by Frida Kahlo. Image courtesy of the Frida Kahlo Foundation.

It would be a mistake, however, to limit consideration of people’s strengths and talents to only those that are directly relevant to success at school or on a job. Most people want to embody and share different sides of themselves; that is, they seek multiple ways to demonstrate their strengths and make contributions to the world. Having a multi-faceted life may even be essential to living a fulfilling life. Can we envision people with extensive or pervasive support needs in non-vocational and non-student roles? Can we envision them as artists, preachers, chefs, gardeners, travel enthusiasts, athletes, sports fans, or in any other culturally valued role that grows and asserts itself from an inner passion? Can we encourage people with extensive or pervasive support needs to develop their strengths in ways that enable them pursue life experiences that truly enhance their quality of life? A story from Psychology’s history shows what can happen when people with intellectual disability are allowed to discover their dormant/hidden/undervalued strengths.

In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, a group of adolescent girls and women with developmental disabilities were living at a state institution in Iowa with nearly 2,000 other residents. Near to the institution was a severely overcrowded and understaffed state-run orphanage. The orphanage was in dire straits due to a perfect storm of an increasing number of destitute women who simply did not have the means to take care of their babies, a decreasing number of families that were in any economic position to adopt, and a dearth of public funding for human services. Infants at the orphanage were failing to thrive physically and intellectually due to a lack of stimulation. With literally no room to place another baby, two infants (15 and 18 months old) who showed signs of significant developmental delays were temporarily moved to women’s cottages on the grounds of a state school in Iowa. Dr. Skeels (1966), who chronicled the events, recalled, “The youngsters were pitiful little creatures. They were tearful, had runny noses, and sparse, stringy, and colorless hair; they were emaciated, undersized, and lacked muscle tonus or responsiveness. Sad and inactive, the two spent days rocking and whining” (p. 5).

Video still taken from a documentary titled “In Our Care: Glenwood State Hospital and School” produced in 1952. Retrieved from YouTube.

Six months after placement, Dr. Skeels (1966) visited the wards of the institution where the babies had been left. He observed two toddlers “smiling, running about, responding to the playful attention of adults and looking like any other toddlers” (p. 6). He did not recognize them as the two “pitiful” babies that had been sent from the orphanage a little over a half of a year ago. He returned to the orphanage, which was in every bit of disarray as it was six months earlier, and concluded “There seemed to be only one alternative, and that a rather fantastic one; namely to transfer mentally retarded children in the orphanage nursery, one to two years of age, to an institution for feebleminded in order to make them normal” (Skeels & Dye, 1939/2002, p. 21).

Dr. Skeels convinced the State of Iowa to allow him to identify the infants with intellectual disability in the orphanage. Half were sent to the institution (the experimental group) and half remained at the orphanage (the control group). A follow-up two years later showed the experimental group infants were thriving while the control group infants were languishing (Skeels & Dye, 1939/2002). The experimental children lost their diagnosis (i.e., they no longer met deficit criteria for intellectual disability) and 12 of the 13 were adopted by families. When the children from the two groups were contacted 25 years later, all of the experimental group children were found to be self-supporting adults, compared to only 4 of the 12 control group children (Skeels, 1966).

Psychology was still a relatively young field at the time of Dr. Skeels’ study, and by today’s standards his research was significantly flawed in terms of scientific rigor. Many would suggest it was flawed ethically as well (How could they leave half of the children in the orphanage, knowing that they would be neglected?). From a research standpoint, the biggest problem was that data collection and analyses were overly focused on IQ score changes; infant and early childhood IQ scores are notoriously unreliable, and therefore IQ was not valid as a dependent measure. However, despite questionable data, Dr. Skeels’ main conclusion was spot on. Namely, babies need stimulation and human contact (e.g., touch, affection) to flourish. Neglectful early environments can result in a failure to thrive with long-term effects. Dr. Skeels deserves credit for influencing a line of research targeted to understanding how experiences and conditions early in life can affect future physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development.

Unfortunately, very little is known about the women who cared for these neglected babies. But, what is known is both beautiful and heartbreaking. Skeels and Dye (1939/2002) reported that each child was placed on a ward that included 30 institutional inmates (this was term used at the time for institutionalized adults) who they described as older girls, and one attendant (there a was staff hierarchy, with matrons and assistant matrons in charge of the wards, and attendants were the lowest level of employee). We also know that “in the case of almost every child, some one adult (older girl or attendant) would become particularly attached to a given child and would figuratively ‘adopt’ him” (p. 25). But, everyone contributed. “The girls would spend a great deal of time with the children, teaching them to walk, talk, play with toys and play materials, and in the training of habits. Most of the clothing for these children was made by the older girls. The girls were so fond of the children that they would actually spend their small earnings and allowances to buy them special foods, toys, picture books, and materials for clothing” (p. 24).

Unfortunately, very little is known about the women who cared for these neglected babies. But, what is known is both beautiful and heartbreaking. Skeels and Dye (1939/2002) reported that each child was placed on a ward that included 30 institutional inmates (this was term used at the time for institutionalized adults) who they described as older girls, and one attendant (there a was staff hierarchy, with matrons and assistant matrons in charge of the wards, and attendants were the lowest level of employee). We also know that “in the case of almost every child, some one adult (older girl or attendant) would become particularly attached to a given child and would figuratively ‘adopt’ him” (p. 25). But, everyone contributed. “The girls would spend a great deal of time with the children, teaching them to walk, talk, play with toys and play materials, and in the training of habits. Most of the clothing for these children was made by the older girls. The girls were so fond of the children that they would actually spend their small earnings and allowances to buy them special foods, toys, picture books, and materials for clothing” (p. 24).

Video still taken from the documentary “In Our Care: Glenwood State Hospital and School” produced in 1952. Retrieved from YouTube.

The pitiful infants certainly brought a priceless gift with them to the institution. Namely, they offered those who were willing to love them the opportunity to discover their own strengths and talents, and to find additional meaning in their own lives. What a delightful change of pace it must have been to have a baby on the ward to love and to hold. What joy these babies must have brought to their temporary mothers. In Man’s Search for Meaning, Victor Frankl (1992) explains how he survived the Holocaust by finding personal meaning through his experiences. He writes:

Being human always points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself – be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself – by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love – the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself (p. 115).

Psychiatric Hospital of Schönbrunn, 1934. Photo by Nazi Party SS member, Friedrich Franz Bauer

After 2-3 years at the institution, the toddlers were removed and returned to the orphanage because they were now perceived to be promising candidates for adoption. Did the mothers take pride in the work they had done? Did they celebrate the fact that they had provided their child with an opportunity for adoption by a family? Were they even aware that this was the child’s likely fate? Or, was a child, who was loved dearly by a group of women, taken away from them without much explanation? Did any of them question why, despite their efforts and success, they were no longer considered to be worthy to be mothers, or even provided opportunities to maintain their relationships with these children?

Skeels and Dye’s (1939/2002) famous study offers little to us today in terms of guidance in regard to child development. There is far more solid research documenting the importance of optimizing the early years of a child’s life. The most relevant lesson we can take away from their study concerns the importance of understanding people with disabilities by their strengths and seeing their potential to enhance the lives of others with whom they are associated. The women from the Glenwood State School were briefly provided an opportunity to discard their identities as institutional inmates, and discover their strengths as healers and mothers.

Art work by Aoife Hyland Sidener, 6th grade middle school student, Kansas.

In the Strength Based Inclusive sequence the efforts of students and faculty members coalesce around research agendas that bring to light the strengths and gifts of people with extensive and pervasive support needs. We strive to prepare future educators to see past disability labels while recognizing and fostering the talents of their students. As long as the faculty and students in our doctoral program sequence remain true to these ideals, it is probably OK if we continue struggle to correctly recall the full name of our sequence.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Frankl, V. E. (1992). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (4th ed.). Beacon Press: Boston, MA. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/MansSearchForMeaning-English

Skeels, H. M., & Dye, H. B. (1939/2002). A study of the effects of differential simulation on mentally retarded children. Proceedings of the American Association on Mental Deficiency, 44, 114-136. Reprinted in J. Blacher & B. Baker (Eds), The Best of AAMR: Families and Mental Retardation: A Collection of Notable AAMR Journal Articles Across the 20th Century. American Association on Mental Retardation: Washington, DC.

Skeels, H. M. (1966). Adults status of children with contrasting early life experiences: A follow-up study. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 31 (3, Series No. 105).

Bio

James R. Thompson, Ph.D. has over 30 years of experience in the field of developmental disabilities as a direct support professional, special educator, rehabilitation counselor, teacher educator, and researcher. He has authored or co-authored over 70 books, book chapters, monographs, and articles in professional journals, and has directed multiple federal and state funded research and model demonstration projects. His primary research focus for the past 15 years has been on support needs assessment and planning with children and adults with intellectual disability and related developmental disabilities. He is the lead author of American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities’ Supports Intensity Scales (both the adult version and the children’s version), the first assessment tools to provide standardized measures of the support needs of people with disabilities. The Supports Intensity Scales have been translated and published in 13 languages, and are being used throughout the United States and world. Jim serves as Editor of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Dr. Thompson serves as a Professor in the Department of Special Education, Senior Scientist at the Beach Center on Disability, and Associate Director of the Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities. He has previously served on the Board of Directors for the AAIDD and the Council for Exceptional Children’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Division. He currently serves as Editor of the professional journal, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Beyond Location: Education for Travellers as an Irish Ethnic Minority

Máirín Kenny, PhD, is a former teacher, principal and educator who has worked for over thirty years with students and parents from the Irish Traveller community, a recognized indigenous ethnic minority within Ireland. Dr. Kenny is currently an independent scholar and conducts commissioned research on equality, disabilities, ethnicity, racism, and sectarianism in Irish education. Hawk Hopes Blog invited Dr. Kenny to share some perspectives on what it means to be an agent of change within the Irish educational context. Here is what she had to say. —Sorcha Hyland

Who are the “Irish Travellers”?

Irish Travellers have been a distinct group in Irish society since at least the twelfth century. They are Irish, but a recent human genome research project has shown them to have been genetically separate since at least the sixteenth century. And only this year they won recognition in Irish law as an ethnic group—a status they have had since 2000 in Northern Ireland (under UK law). There are ethnic populations all over Europe, similar to the Irish Travellers. It is officially recognized that these peoples are targets of the most virulent racism across Europe. There are Irish and European people who will accept immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers—but not the Travellers, or the Roma.

The Irish Travellers’ economic activities married well with nomadism. They turned their hand to whatever trade or service was required and could cover a territory large enough to survive. They traded in horses and donkeys, they worked as blacksmiths (shoeing horses and donkeys), and tinsmiths (making and mending tin cans, buckets, basins—hence their older name “tinker”, a term that acquired pejorative racist meanings). And in the days before village shops, they hawked— selling small domestic goods such as wool and kitchen utensils. Irish Travellers included all sorts of traders who could provide a range of mobile services to a wider territory than the sedentary working population could feasibly cover. In the twentieth century, they turned to trading in second-hand goods, scrap metal, gardening, etc. But the space for these services has shrunk. And at the same time, they are virtually shunned in the employment market—currently, unemployment among Travellers runs at above 70%.

The question “who are they?” is a good one. It never struck the dominant Irish settled population to ask that question—still less did it strike us to ask the Travellers that question. In the early 1960s, prominent social activists discovered the plight of this group—a population of about 6,000, living on the roadside in miserable tents and wagons, with no services, scant access to health or education services, a life expectancy of 30 years, and an infant mortality rate seven times the national rate. But these leaders, and the government, once stirred to action, assumed that these people were dropouts, perhaps descended from homeless peasantry in Famine times. And the solution was to settle them down, clean them up, and fit them in.

In a negative sense, nomadism also shaped everything. In Ireland (and in the UK and elsewhere), Irish society and social structures (law, housing policy, etc.) have traditionally used nomadism as a tool to destroy the nomad: historically, they were needed but not wanted by local communities. Once the work was done, the Travellers had to move on; and at an official level roadside camping was made illegal. In short, the timing of their movements was dictated by the settled population, and the conditions for dignified nomadism were cut from under them, where they existed at all. Very few of them are now nomadic, and even fewer want to be so.

In a negative sense, nomadism also shaped everything. In Ireland (and in the UK and elsewhere), Irish society and social structures (law, housing policy, etc.) have traditionally used nomadism as a tool to destroy the nomad: historically, they were needed but not wanted by local communities. Once the work was done, the Travellers had to move on; and at an official level roadside camping was made illegal. In short, the timing of their movements was dictated by the settled population, and the conditions for dignified nomadism were cut from under them, where they existed at all. Very few of them are now nomadic, and even fewer want to be so.

But when they try to settle, they are still in the wrong “place”. Housing policies have driven them into standard accommodation (hugely inappropriate and inadequate), and those who move now do so because they can’t find anywhere to live. Everyone wants them to stop travelling, but not to stop it “here”—Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY-ism).

Today, there are perhaps 40,000 Irish Travellers. Theoretically they have access to all the social services, but racism still raises its ugly head to narrow that. They nearly all stay in school until age 15 years, but that is shockingly far below the completion level for the general population—the education system is failing them more than any other sector. Their life expectancy is 11 years below the national average for women, 15 below for men. Infant mortality is over three times the national average. Suicide rates for men are seven times the national rate, and for women 4.5 times the rate.

Why did you choose to work in school provision for Irish Travellers specifically?

When I chose to work with the Irish Travellers I also thought they were at the extreme end of rural disadvantage—so marginalized that they were homeless. I think I quickly realised that was far from the whole story—if it was part of the story at all.

As a teacher, and later principal in a school for Irish Traveller children, and as a sociologist I was very interested in educationally disadvantaged populations. From the get-go, I wanted to work with people who were experiencing marginalization. I wanted to learn more about and with the people who were being forced to operate in the fringes of the Irish public education system.

Nan Joyce, Irish Traveller activist and spokeswoman, 1984. Photograph by Eamonn Farrell. Published in http://www.thejournal.ie, March 1, 2017.

What have you learned from your professional experiences both as an educator, a principal and a researcher in relation to Irish Travellers?

It took me a lot of work to really get it that the Irish Travellers are a people with a distinctive identity and approach to life. And one that I have grown to understand and respect hugely. In 1978 I became principal of a school that had been set up entirely for Travellers. Then, the idea didn’t seem as shocking as now! And, I developed an agenda for it—two long-term aims, and once they were achieved, the school should go.

First of all, I argued that like any silenced group, Travellers needed their own space to find their voice, and to read their world, to reclaim their pride, and reflect on their situation—free, for as long as necessary, of the hostile gaze of the oppressor. I think Liégeois (a French specialist on Roma and Travellers in Europe) had a point when he said that the paradox facing Travellers was that they had to enter the house of the oppressor to gain the tools to end their own oppression.

Secondly, I was very concerned with an unspoken notion that I saw at least implicit in education policy towards them– that “Traveller culture” is a euphemism for poverty or deviance. A submerged racism. And among Travellers, there was a mirror-version of that—expressed often in the words “how can Travellers all in together learn anything?” I wanted the school to prove that Traveller culture provided a rich space for a proud and distinct school identity and curriculum, and that Travellers all in together could learn, could go from there to any school of their choice, as good as any child or youth from any other school in the town. In my school, the children could be openly Traveller, and they go on into local secondary (=middle/high) schools, well able to state their case, challenge racism and say why it was wrong. But at the same time, I know that there was a larger structural lesson being learned: the students were Travellers, and were being kept separate.ut at the same time, I know that there was a larger structural lesson being learned: the students were Travellers, and were being kept separate.

However, the mainstream Irish public education system is just not flexible or intuitive enough yet to take in all the different perspectives that ethnicity in Ireland presents. In theory and even in practice, we know where we need to get to. In terms of securing the kind of national and international support necessary to ensure all students, of all ethnicities, have access to fair and culturally appropriate free public education—Ireland– like other European Union member states, like other developing and industrialized and even post-industrialized nations—has a way to go yet. But I think school provision is the wrong place to start.

What has your practice in the field, and your research revealed to you?

The huge thing I have learned – when approaching populations who have been marginalized to the extent that Irish Travellers are –severely disadvantaged, encountering multigenerational cycles of unemployment…the attitude of the dominant education or academic community is often misplaced. The focus tends to be “Let’s get to the children and rescue them first”. I have learned that it can’t work this way. That this way of remediating a human rights problem, particularly involving children and youth from ethnic minorities, does not work. In my experience here you can’t work with the children if you don’t work with the community that envelops the children. In a human rights framework. If the parents are empowered and enabled, if we make a space where they can explore possibilities beyond what has been allowed or offered to them before– then they—the parents, the grandparents, the family members, the guardians and caregivers from within the marginalized population—will make sure the children get the best that they can get.

Traveller boys in Dublin, Ireland, 1980. Photograph by Brian Palm.

Our focus needs to shift to not just parental access to education, or parental rights in education, but to creating meaningful and culturally responsive parent-professional interactions where parent-driven professional learning and development can occur. As opposed to teachers working solely with children from populations where they have no prior knowledge or understanding of that population as a living ethnic minority, an evolving culture. Or where they have no professional preparation in critical and culturally reflexive and responsive practices to inquire and learn about the cultures their students and families bring to the classroom.

How are Irish Travellers impacted by other international realities, such as state, EU- and UN-driven incentives around inclusive and special education, if at all?

Irish Traveller girl, 1965. Photograph by Alen MacWeeney (b. 1939) from his publication Irish Travellers: Tinkers No More (2007).

In the 1960’s, once it was discovered that Irish Traveller children and youth were not going to school on any kind of a consistent basis, activists campaigned to have resources available to them within the special education system (the only avenue to augmented resources available at the time). This was a strategic move, tempting for well-intentioned educational activists. The objective was to intensively up-skill these children, prior to “absorbing” them in the “normal” classes . But the children didn’t move on. Not until the inclusion movement of the 90’s. And then— (beware of what you pray for, you might get it)—in 2007, the Irish Department of Education produced Notes towards a Traveller Education Strategy. Combining the inclusion principle with the need to cut back expenditure, the Department axed all home-school and resource-teaching provision for Travellers. In future, Traveller children would access resources on the basis of need, not identity. How to separate the good from the bad in that statement!?

As regards special education generally, since the 1970’s Ireland has become increasingly influenced by international frameworks of thinking across Europe and more globally as inclusive education, in all its variants, has become the name of the game. This too can be a risky thing. The ideal of inclusive education can only be realised if, in the transition from special provision, the child in question loses nothing of the resources and supports they received in that provision. Truly inclusive education, in any context and of any variant, has got to be more expensive. It must entail additional services and supports and professional training that enable the modern, “inclusive” classroom to be truly universal. At a policy level across EU and in Ireland – we continue to see merely locational inclusion – the placement of children with special needs and/or with generational obstacles to education access all thrown together, in the name of inclusive education. This is not building inclusion. This is in fact worse than exclusion. This is a cost-saver.

How do you distinguish between good versus bad, or even ‘not so good’ practices of inclusive education, in the contexts you focus on?

Locational inclusion is merely a body-count. Are they in the same room? All day? If yes—job done. But real inclusion is making sure every child that is in the room owns the place, belongs. They must feel enabled to operate to the best of their ability within that setting. For example, true inclusion would enable children to access a space where they could remove themselves from a larger group, read, or relax, or sail their boat within the majority classroom. Inclusion must be elastic and modular. It must have a continuum of provisions. All students, including Irish Traveller students, need supports. They all need spaces to draw their breath. All children have the right to the tools and the supports necessary to enable them, in their bodies and with their unique strengths and challenges, systemic or biological, to find their way within the majority classroom. That is inclusion.

How do you describe the educational system in Ireland in general terms?

The general education system in Ireland is too rigid. We should have a continuum of provision so our students, from all ethnicities, with all levels of forms of learning and ability, can operate wherever they need to be to speed ahead or go at their own pace with their own lives. So, if a child needs a lot of physical therapy within the given school-day, they can have this provision within the system and no obstacles in terms of when or how they re-join their peers or class cohort. Our hidden curriculum, not unlike that in the United States, is definitely one of competition and survival of the fittest. At the end of the day you come out of education with or without the piece of paper you need to get into third level (institutes of higher education). There is an undertow separating people for the purposes of economic stratification, that informs the Irish and it seems, most Western public education systems.

Teachers in the Irish public school system are academically bright, highly qualified, and respected in the community with a very strong tradition of successful unionization. The primary (in U.S. terms “elementary”) school teaching force is trained to teach all students aged 4-12 years, not bifurcated into “general” or “special”. But they are almost all middle class, white, and indigenous. Given the rapidly growing ethnic diversity in Irish society, and the movement to inclusive education provision (under-resourced of course), Ireland needs a more diverse teaching force, and substantial investment in relevant, high-quality initial teacher education and continuing professional development.

Where else might the Irish public education continue to evolve, in your opinion?

In the Irish public education system, we need to continue to grow in parent-teacher communication and partnerships. Both on a whole school basis and to face the challenges that arise as new shifts and unexpected realities emerge from our societies at large. The huge increase in diversity in Irish society, over the course of my own career and especially over the last 15 years points to the impact that forced migration, including economic migration, has had on Irish society. Along with that front-end challenge, the system of educational organization has to become more flexible, it has to move beyond its own hidden curriculum and narrow cultural focus.

It is good to see the education partnership growing, where parents, teachers and children become partners in the whole education process. The move towards inclusive education is very good, but it is grossly under-funded. Parents and caregivers in Ireland are no longer sitting on the sidelines. They have become much more vocal.

How did your doctoral work inform your understanding of educational practice and educational leadership in the Irish system?

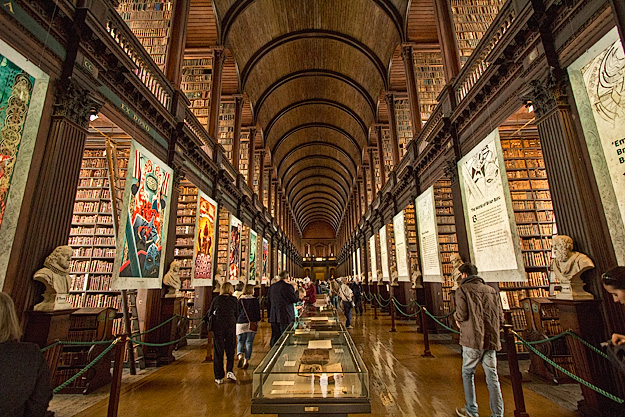

I did my doctorate in sociology in Trinity College Dublin while I was still teaching. I was a graduate student, a school principal, and a classroom teacher simultaneously. I went into research to try to figure out what were we missing in what Travellers themselves had to say about education, and in how they used language to describe what they were “not”. I love research and I love trying to understand what people say and how that relates to policy.

Equality, equity and the belief that everyone has the right to have access to whatever supports they need to do the best they can informed my position. We should never allow a structural block to limit a person’s potential. That structural block might be a door that isn’t wide enough to allow someone on wheels or using alternative mobility supports to enter, or a system that does not reach out to where people really are. I see no value in just saying “We are very inclusive. So you can now come to us”. If people have centuries of experience behind them, where they know, are told, and experience that they are not welcome – it is not enough for a state institution to just change its mind and say “come on in”. The system must go out to the people, it must reach out to the communities that have experienced marginalization, discrimination, exclusion, oppression – and learn how to include them.

From the designers of educational curricula all the way up to the policy maker– we must know who we have omitted/are omitting, we must reach out to them, learn about them, inform the system how to fully recognize and include them (Bryan, 2010) – to ever proclaim “nothing about us without us”, or “all means all”, or “everyone is welcome”. This is their right.

Otherwise we just sound patronizing.

Bio

Máirín Kenny, PhD, is a former teacher, principal and educator who has worked extensively and for over thirty years with students and parents from the Irish Traveller community, a recognized indigenous ethnic minority within Ireland. She is currently an independent scholar. Dr. Kenny has conducted commissioned research on equality, disabilities, ethnicity, racism, and sectarianism in Irish education. She co-edited Traveller, Nomadic and Migrant Education (Routledge, 2009) with Patrick Danaher (University of Southern Queensland). She authored a chapter for Education in Indigenous, Nomadic and Travelling Communities (Eds: R. Griffin and P. MacÉinrí. Bloomsbury, 2014); and co-authored a chapter for Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (Eds: AK Schulte & B Walker-Gibbs. Springer, 2016). Most recently, she co-authored a book chapter on special education in the Republic of Ireland for The Praeger International Handbook of Special Education (Eds: M. Wehmeyer & J. Patton, 2017) with Dr. Thérèse McPhillips (St. Patrick’s College, Ireland), Sorcha Hyland (Department of Special Education, University of Kansas) and Dr. Michael Shevlin (Trinity College Dublin, Ireland).

References

Bryan, A., (2010). Corporate multiculturalism, diversity management, and positive interculturalism in Irish schools and society. Irish Educational Studies, 29(3), pp. 253-269. http://doras.dcu.ie/21480/

Liégeois, J. P. (1994). Roma, Gypsies, Travellers. Council of Europe.

Watson, D., Kenny, O., & McGinnity, F. (2017). A Social Portrait of Travellers in Ireland. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin, Ireland.

Beyond the Schoolhouse to Systems Change: Transformation Through Inclusive Leadership

By Cynthia Mruczek

Yayoi Kusama. Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away. 2013. Wood, metal, glass mirrors, plastic, acrylic panel, rubber, LED lighting system, acrylic balls, and water. 113 1/4 x 163 1/2 x 163 1/2 in.

Over the course of an almost-20-year career teaching in public schools and in higher education, I have had the privilege of working with all kinds of people. Some of these individuals have become my nearest and dearest friends. Others float on the periphery of my life—coming into focus every so often to exchange well wishes or compliments on one another’s families. Others…well, our professional relationship ended with new positions or life events that sent us down different paths. I am thankful for each of these relationships—they have all brought me valuable insights on teaching, learning, working with kids, and curricula. Most recently, my career path led me to accept the role of coordinator of the Leadership in Special and Inclusive Education Graduate Certificate (LSIE) at the University of Kansas. This position involves considerable collaboration—and a new learning curve where I continue to draw on the successes and failures that have shaped my career to date. Here, I highlight what I have learned in my work with others to create more inclusive school communities and reflect on what has been missing in our collective leadership efforts.

As a former special education teacher, a general education teacher, and teacher-educator, I have always held the belief that students with disabilities need to be fully included in the general education classroom. As the product of a relatively traditional special education undergraduate program, this was my initial definition of what “inclusion” entails. I relied largely on where students should physically and situationally receive services, as opposed to a more complex understanding of the habits of thinking and attitudes that produce and sustain inclusive education as a practice and a school culture. Luckily, I was encouraged to explore this deeper definition by my own teacher-mentors, and through formal and informal professional learning opportunities, often prompted by lunch room conversations with other colleagues. Led primarily by my former principal (let’s call her “KD”) — my fellow staff members and I were encouraged as a group to “reflect, refine, and reach higher” in our collective understanding of how to best meet the needs of all students, including students with disabilities.

We worked with students who experienced an array of challenges that moved beyond any categorical understanding of “ability”— poverty, discrimination, and learning English as a second language in an English Only state to mention but a few. In the midst of these realities, KD encouraged us to think about what we could do differently. She inspired us to move beyond pathologizing or situating the problems in the students and their families. She encouraged—or really required us—to think about the positive relationships we needed to build with all children and how to create a culture where there was always “someone who really loved them” at school.

We certainly were not perfect and we encountered many challenges. Yet, with this as our primary mission, we made great strides in creating a school climate where many of our students were happy and comfortable. It showed in their achievement levels and their behaviors. For example, we had a number of kids who challenged gender norms through their dress and attitudes. Some “came out” directly as lesbian or gay with virtually no reaction, and in essence full acceptance, from the staff and student body. As educators and role models, we had many important conversations about “identity.” We considered how we positioned ourselves as individuals as well as how our identies impacted our classrooms where the majority of kids we worked with were racially, ethnically, and linguistically minoritized. In my current role as the LSIE coordinator—many may imagine I have a skewed, if not a romanticized vision of what a school can achieve. However in hindsight and in reality, I have had first-hand experience of the kind of magic strong leadership and inspired educators can produce. I have observed and experienced what students—all students—can achieve when they are allowed to feel included in their own success. This “magic” validates and underscores my belief that inclusive practices work and produce the best outcomes for all students, especially students with disabilities.

Allan Rohan Crite. School’s Out. 1936. Oil on canvas. Photograph taken by Sorcha Hyland courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, May 2016. As the label associated with the exhibition of this painting noted, it represents a romanticized view of the Everett elementary school in Boston’s South End and captures Crite’s life-long efforts to challenge stereotypical depictions of Black communities.

As is the norm, many of us in this magical school, under the leadership of KD, moved on to new positions and other opportunities. Yet I continue to return to the stories and strategies I gained from this period in my career to inform my current work in preparing future teachers and administrators. After I left this school, I continued to have many pivotal experiences that further pushed me to think critically about our efforts, and more importantly, to imagine “what could be.” My understanding and definition of an inclusive school is, now, more than ever, primarily focused on social justice. Scholars well-known to KU SPED, Waitoller and Kozleski (2013, p. 35), define inclusive education as,

[T]he continuous struggle toward (a) the redistribution of quality opportunities to learn and participate in educational programs, (b) the recognition and value of differences as reflected in content, pedagogy, and assessment tools, and (c) the opportunities for marginalized groups to represent themselves in decision-making processes that advance and define claims of exclusion and the respective solutions that affect their children’s educational future…

Under KD’s visionary leadership, we made headway on the “redistribution of quality opportunities to learn” while we strived to develop our abilities to better include parents and families in the decision-making process. This remains an ongoing learning process in light of the very structured and standardized educational climate in which public schools across the nation are situated. Visionary and inclusive leadership is not easy. There were times under KD’s leadership when we attempted to enact school-wide reform efforts only to be stopped in our tracks by competing district or state-driven policies.

Under KD’s visionary leadership, we made headway on the “redistribution of quality opportunities to learn” while we strived to develop our abilities to better include parents and families in the decision-making process. This remains an ongoing learning process in light of the very structured and standardized educational climate in which public schools across the nation are situated. Visionary and inclusive leadership is not easy. There were times under KD’s leadership when we attempted to enact school-wide reform efforts only to be stopped in our tracks by competing district or state-driven policies.

A framework for systems change (Kozleski, King Thorius, and Smith, 2014) would have been critical in our work, in order for us to adapt to and navigate the complexities involved in engaging multiple, intersecting activity systems. In order to work towards more socially just and equitable results for all students, particularly those at the margins of participation (e.g., students with dis/abilities, those learning English, kids from undocumented families, etc.)—a systems change framework would have been paramount to our efforts.

Further learning was needed for us to understand the multifaceted aspects of our own intersectional identities too and equally, to recognize the intersections our students also navigated and experienced (Crenshaw, 1991). Such frameworks, and an emphasis on intersectionality, would have equipped us to better deconstruct and understand how power and privilege could further marginalize and oppress our school culture, ourselves as teachers, and most importantly our students who came from communities where generations experienced marginalization and oppression first hand.

We made great strides, but not without a lot of challenging and emotionally charged work that had to be done. As I reflect back on our successes and where we fell short – I am, as I know many of my former colleagues are, very proud of the work we, and our students, collectively accomplished at that school. Yet I am again reminded, as Kozleski and Huber (2012) note, that transforming one school is insufficient. As the coordinator of the Leadership in Special & Inclusive Education Graduate Certificate at the University of Kansas Special Education Department(KU SPED), we now have a program that can fill a critical and an important need across many, if not all, school communities.

Street poster art curated and produced by children in a “guerilla art camp”, facilitated and taught by the Lawrence Arts Center, Lawrence, KS. Photograph courtesy of Sorcha Hyland.

The KU SPED LSIE Graduate Certificate is designed to address the needs of not just one school, but of an entire system of schools. Our mission is to provide school leaders and administrators with the tools, knowledge, and habits of thinking they need to build a very solid background in special education law and policy, in the context of creating more inclusive school cultures. LSIE positions and prepares professionals from all sectors of school administration—to lead sustainable reform efforts at multiple levels of the public education system. The readings cited in this blog, for example, are indicative of the kind of critical thinking and research-based discussion that LSIE offers its student participants as they learn what it means to become leaders in the field of cutting-edge inclusive education practices, not just in the United States, but internationally.

Elizabeth Kozleski (Chair), Michael Wehmeyer & Ann Turnbull, leaders in inclusive education practices from the University of Kansas Special Education Department. Professor Kozleski developed, leads and also video-presents in the LSIE program, with Tom Skrtic pictured below.

This 32-week program is designed as a highly innovative, professional online learning experience where state-of-the-art processes such as game simulation of district-level decision-making, interactive discussion boards, and intensive instructor-student and peer-to-peer interactions are used to build deep, collaborative learning opportunities. Participants who successfully complete this online KU SPED Graduate Certificate are fully equipped to advance the rights of all students, confront biases about special education and other historically marginalized populations, and overcome implementation challenges of inclusive and special education policies in systemic and sustaining ways.

University of Kansas Special Education Distinguished Professor, Thomas Skrtic, conceptualized the LSIE program, and also video-presents key constructs and themes throughout.

In closing, I ask that if any aspect of this story resonates with you – if you are in a leadership position in a school or district, if you hope to be in a leadership position someday, if you are searching for more socially just opportunities for all students, or you are interested in understanding the research on the leading edge of inclusive schools –check out our LSIE Graduate Certificate. Join us to work towards reforming and transforming not just “one” school, but our whole school system as we lead and educate to advance the rights of all students.

References

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.