By Cynthia Mruczek

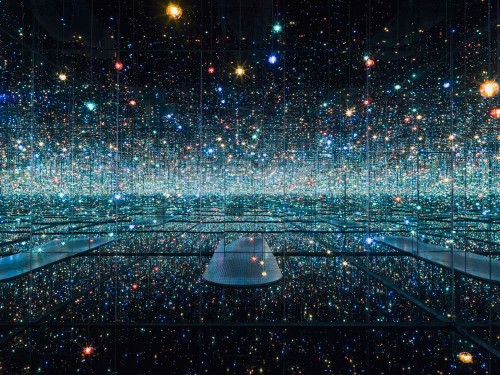

Yayoi Kusama. Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away. 2013. Wood, metal, glass mirrors, plastic, acrylic panel, rubber, LED lighting system, acrylic balls, and water. 113 1/4 x 163 1/2 x 163 1/2 in.

Over the course of an almost-20-year career teaching in public schools and in higher education, I have had the privilege of working with all kinds of people. Some of these individuals have become my nearest and dearest friends. Others float on the periphery of my life—coming into focus every so often to exchange well wishes or compliments on one another’s families. Others…well, our professional relationship ended with new positions or life events that sent us down different paths. I am thankful for each of these relationships—they have all brought me valuable insights on teaching, learning, working with kids, and curricula. Most recently, my career path led me to accept the role of coordinator of the Leadership in Special and Inclusive Education Graduate Certificate (LSIE) at the University of Kansas. This position involves considerable collaboration—and a new learning curve where I continue to draw on the successes and failures that have shaped my career to date. Here, I highlight what I have learned in my work with others to create more inclusive school communities and reflect on what has been missing in our collective leadership efforts.

As a former special education teacher, a general education teacher, and teacher-educator, I have always held the belief that students with disabilities need to be fully included in the general education classroom. As the product of a relatively traditional special education undergraduate program, this was my initial definition of what “inclusion” entails. I relied largely on where students should physically and situationally receive services, as opposed to a more complex understanding of the habits of thinking and attitudes that produce and sustain inclusive education as a practice and a school culture. Luckily, I was encouraged to explore this deeper definition by my own teacher-mentors, and through formal and informal professional learning opportunities, often prompted by lunch room conversations with other colleagues. Led primarily by my former principal (let’s call her “KD”) — my fellow staff members and I were encouraged as a group to “reflect, refine, and reach higher” in our collective understanding of how to best meet the needs of all students, including students with disabilities.

We worked with students who experienced an array of challenges that moved beyond any categorical understanding of “ability”— poverty, discrimination, and learning English as a second language in an English Only state to mention but a few. In the midst of these realities, KD encouraged us to think about what we could do differently. She inspired us to move beyond pathologizing or situating the problems in the students and their families. She encouraged—or really required us—to think about the positive relationships we needed to build with all children and how to create a culture where there was always “someone who really loved them” at school.

We certainly were not perfect and we encountered many challenges. Yet, with this as our primary mission, we made great strides in creating a school climate where many of our students were happy and comfortable. It showed in their achievement levels and their behaviors. For example, we had a number of kids who challenged gender norms through their dress and attitudes. Some “came out” directly as lesbian or gay with virtually no reaction, and in essence full acceptance, from the staff and student body. As educators and role models, we had many important conversations about “identity.” We considered how we positioned ourselves as individuals as well as how our identies impacted our classrooms where the majority of kids we worked with were racially, ethnically, and linguistically minoritized. In my current role as the LSIE coordinator—many may imagine I have a skewed, if not a romanticized vision of what a school can achieve. However in hindsight and in reality, I have had first-hand experience of the kind of magic strong leadership and inspired educators can produce. I have observed and experienced what students—all students—can achieve when they are allowed to feel included in their own success. This “magic” validates and underscores my belief that inclusive practices work and produce the best outcomes for all students, especially students with disabilities.

Allan Rohan Crite. School’s Out. 1936. Oil on canvas. Photograph taken by Sorcha Hyland courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, May 2016. As the label associated with the exhibition of this painting noted, it represents a romanticized view of the Everett elementary school in Boston’s South End and captures Crite’s life-long efforts to challenge stereotypical depictions of Black communities.

As is the norm, many of us in this magical school, under the leadership of KD, moved on to new positions and other opportunities. Yet I continue to return to the stories and strategies I gained from this period in my career to inform my current work in preparing future teachers and administrators. After I left this school, I continued to have many pivotal experiences that further pushed me to think critically about our efforts, and more importantly, to imagine “what could be.” My understanding and definition of an inclusive school is, now, more than ever, primarily focused on social justice. Scholars well-known to KU SPED, Waitoller and Kozleski (2013, p. 35), define inclusive education as,

[T]he continuous struggle toward (a) the redistribution of quality opportunities to learn and participate in educational programs, (b) the recognition and value of differences as reflected in content, pedagogy, and assessment tools, and (c) the opportunities for marginalized groups to represent themselves in decision-making processes that advance and define claims of exclusion and the respective solutions that affect their children’s educational future…

Under KD’s visionary leadership, we made headway on the “redistribution of quality opportunities to learn” while we strived to develop our abilities to better include parents and families in the decision-making process. This remains an ongoing learning process in light of the very structured and standardized educational climate in which public schools across the nation are situated. Visionary and inclusive leadership is not easy. There were times under KD’s leadership when we attempted to enact school-wide reform efforts only to be stopped in our tracks by competing district or state-driven policies.

Under KD’s visionary leadership, we made headway on the “redistribution of quality opportunities to learn” while we strived to develop our abilities to better include parents and families in the decision-making process. This remains an ongoing learning process in light of the very structured and standardized educational climate in which public schools across the nation are situated. Visionary and inclusive leadership is not easy. There were times under KD’s leadership when we attempted to enact school-wide reform efforts only to be stopped in our tracks by competing district or state-driven policies.

A framework for systems change (Kozleski, King Thorius, and Smith, 2014) would have been critical in our work, in order for us to adapt to and navigate the complexities involved in engaging multiple, intersecting activity systems. In order to work towards more socially just and equitable results for all students, particularly those at the margins of participation (e.g., students with dis/abilities, those learning English, kids from undocumented families, etc.)—a systems change framework would have been paramount to our efforts.

Further learning was needed for us to understand the multifaceted aspects of our own intersectional identities too and equally, to recognize the intersections our students also navigated and experienced (Crenshaw, 1991). Such frameworks, and an emphasis on intersectionality, would have equipped us to better deconstruct and understand how power and privilege could further marginalize and oppress our school culture, ourselves as teachers, and most importantly our students who came from communities where generations experienced marginalization and oppression first hand.

We made great strides, but not without a lot of challenging and emotionally charged work that had to be done. As I reflect back on our successes and where we fell short – I am, as I know many of my former colleagues are, very proud of the work we, and our students, collectively accomplished at that school. Yet I am again reminded, as Kozleski and Huber (2012) note, that transforming one school is insufficient. As the coordinator of the Leadership in Special & Inclusive Education Graduate Certificate at the University of Kansas Special Education Department(KU SPED), we now have a program that can fill a critical and an important need across many, if not all, school communities.

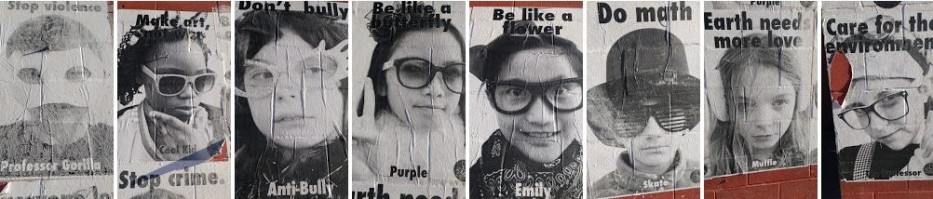

Street poster art curated and produced by children in a “guerilla art camp”, facilitated and taught by the Lawrence Arts Center, Lawrence, KS. Photograph courtesy of Sorcha Hyland.

The KU SPED LSIE Graduate Certificate is designed to address the needs of not just one school, but of an entire system of schools. Our mission is to provide school leaders and administrators with the tools, knowledge, and habits of thinking they need to build a very solid background in special education law and policy, in the context of creating more inclusive school cultures. LSIE positions and prepares professionals from all sectors of school administration—to lead sustainable reform efforts at multiple levels of the public education system. The readings cited in this blog, for example, are indicative of the kind of critical thinking and research-based discussion that LSIE offers its student participants as they learn what it means to become leaders in the field of cutting-edge inclusive education practices, not just in the United States, but internationally.

Elizabeth Kozleski (Chair), Michael Wehmeyer & Ann Turnbull, leaders in inclusive education practices from the University of Kansas Special Education Department. Professor Kozleski developed, leads and also video-presents in the LSIE program, with Tom Skrtic pictured below.

This 32-week program is designed as a highly innovative, professional online learning experience where state-of-the-art processes such as game simulation of district-level decision-making, interactive discussion boards, and intensive instructor-student and peer-to-peer interactions are used to build deep, collaborative learning opportunities. Participants who successfully complete this online KU SPED Graduate Certificate are fully equipped to advance the rights of all students, confront biases about special education and other historically marginalized populations, and overcome implementation challenges of inclusive and special education policies in systemic and sustaining ways.

University of Kansas Special Education Distinguished Professor, Thomas Skrtic, conceptualized the LSIE program, and also video-presents key constructs and themes throughout.

In closing, I ask that if any aspect of this story resonates with you – if you are in a leadership position in a school or district, if you hope to be in a leadership position someday, if you are searching for more socially just opportunities for all students, or you are interested in understanding the research on the leading edge of inclusive schools –check out our LSIE Graduate Certificate. Join us to work towards reforming and transforming not just “one” school, but our whole school system as we lead and educate to advance the rights of all students.

References

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Kozleski, E. B., & Huber, J. (2012). System-wide leadership for culturally responsive education. In J. Crockett, B. Billingsley & M. L. Boscardin (Eds.), Handbook on Special Education Leadership. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Kozleski, E. B., Thorius, K. K., & Smith, A. (2014). Theorizing systemic reform in urban schools. In E. B. Kozleski & K. K. Thorius (Eds.), Ability, equity, and culture: Sustaining inclusive urban education reform (pp. 11-35). New York: Teachers College Press.

Waitoller, F. R. & Kozleski, E. B. (2013). Working in boundary practices: Identity development and learning in partnerships for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 31, 35-45.

Cynthia’s Bio

Dr. Cynthia Mruczek has been an educator for 18 years. She has worked in urban settings as a special and general educator, as well as an instructional coach, serving students from grades three through high school. Her doctoral work was centered on teacher learning and its impact on students of color in urban classrooms. Currently, Dr. Mruczek is currently an Instructor in the Special Education Department at University of Kansas. Her research and consultative work focuses primarily on teacher learning related to issues of equity in the classroom. She has partnered with schools across the country on various topics, including: culturally responsive pedagogy and classrooms, Culturally Responsive Cognitive Coaching and leadership, and building positive teacher/student relationships, among others. Additionally, Dr. Mruczek has partnered with ASU and USAID in providing support for international teacher educators from India and Africa in the area of gender equity in schools. Dr. Mruczek has a strong passion for equity and social justice, which drives her research and partnerships.