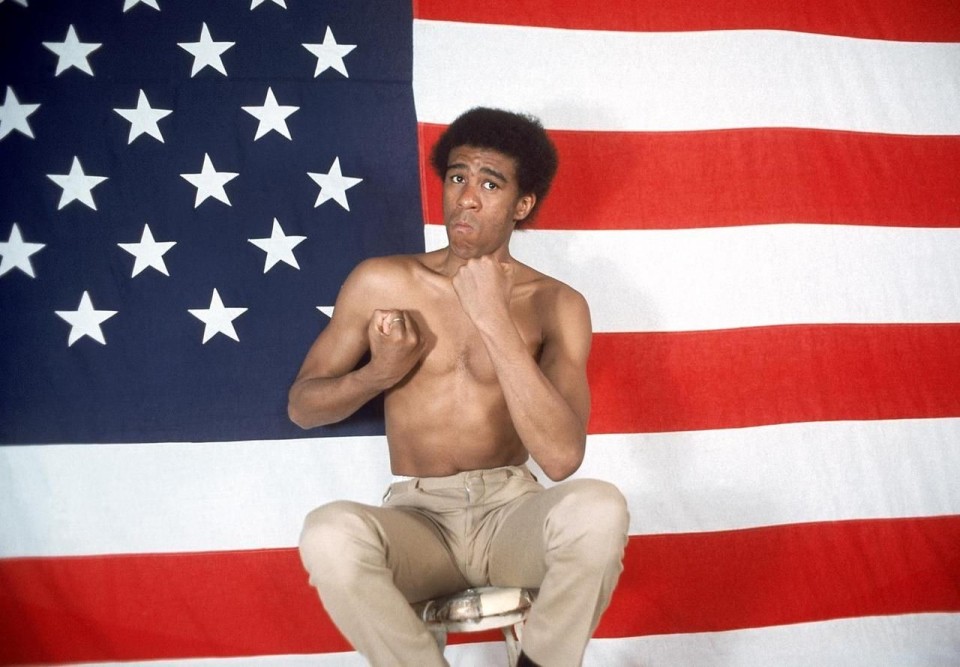

Learning to Listen: “Who Me? I’m Not Him”

By Ray Pence Mizumura, PhD

What I have to say about the late Richard Pryor (1940-2005)—known primarily for breaking racial and racist rules hilariously and fearlessly—might not be a “natural fit” for this Special Education (SPED) space? Yet, from the perspective of a lecturer in American Studies, and with a longstanding scholarly interest in Pryor’s life work— I want to make some “cultural sense” of his significance.

I understand disability in itself as a socially constructed space, where storytelling and narratives that center the lived experiences of disability can change how we learn to understand our world. Such lived experience is always intersectional.

I understand disability in itself as a socially constructed space, where storytelling and narratives that center the lived experiences of disability can change how we learn to understand our world. Such lived experience is always intersectional.

Pryor’s life illustrated the realities of living not just with multiple disabilities but with multiple forms of oppression—and most critically—with multiple strategies for coping if not challenging them.

He did not “overcome” his multiple sclerosis (MS), his heart problems, his depression, or his addictions. Yet Pryor did make sense of them with stories that made people laugh and then go beyond laughter, to witness a remarkable range of emotional and intellectual insight and skill. For this, Pryor was inspirational in the word’s most positive sense, eluding if not challenging the pitfalls that disability pride activists rightly associate with “inspiration porn.”

Pryor’s comedy was profoundly personal and “culturally intimate” (Cooper, 2007). As a white man, Pryor speaks to me. I imagine not in the same ways he may speak to a Black man or another man of color, but in ways I find important enough to share with academic audiences. Pryor’s work, when taken as a serious subject of study, stretches us all to think beyond the hegemonic parameters that frequently dominate in the academy and mirror what we confront or perpetuate societally. Much of what we discuss and write about (or indeed avoid discussing and writing about) in studying the very construct of [dis]ability, manifest in Pryor’s drive to entertain and simultaneously, if not surreptitiously, to inform us about and to challenge the brutality, if not violence inherent in the silence of the status quo.

I first heard Pryor, as a teenager, in the mid-1970s and I am still “learning to listen”, as George Lipsitz theorized it (1990). Pryor’s career was exciting if not a little dangerous for a white boy like me to subscribe to with any level of adoration. On the one hand, acclaim for Pryor as America’s best comic and even the “world’s funniest man” was pervasive. He was a superstar on record, in movies, on television, and especially on stage. On the other hand, Pryor earned success by celebrating blackness while simultaneously subverting white constructs of what being Black entailed. This work was done in full public view of a nation that build itself on the backs of enslaved Black women, men and children, a Jim Crow nation that has yet to fully acknowledge, articulate and make recompenses for its genocidal history.

Pryor’s remarkable capacity to play out these intersections could, of course, be reduced to performing genius. However to pigeon-hole him as purely this is to fail to acknowledge his intellect, his political skill, and most critically his determination to seize cultural and historical moments in what Jacquelyn Dowd Hall calls “the long civil rights movement” (2005).

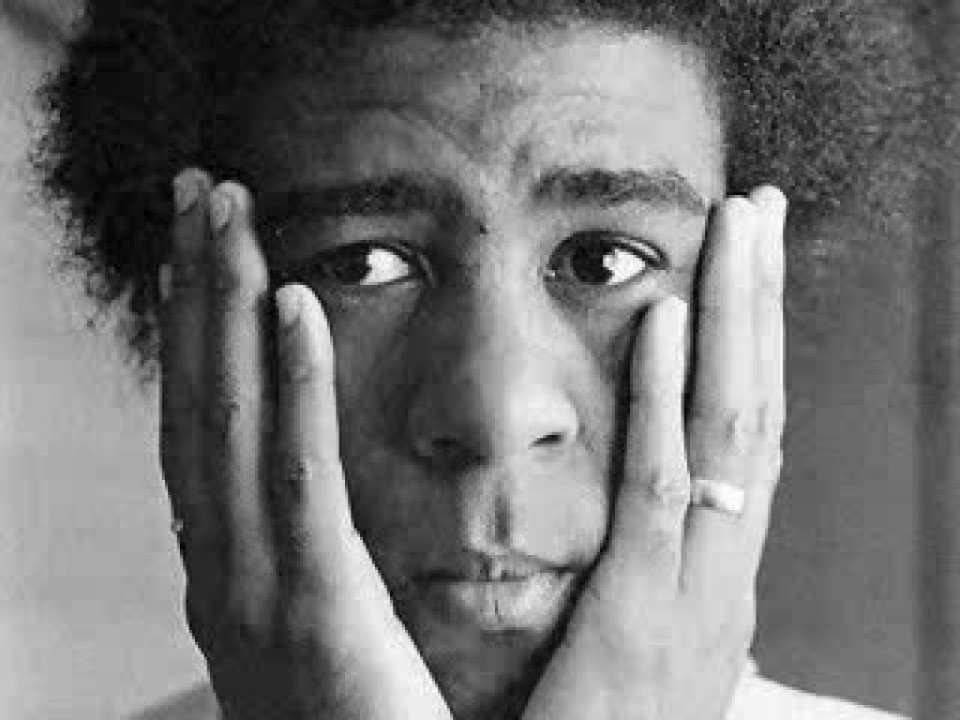

Great commercial success does not bring total security—especially for those whose bodies are marked as threatened and threatening. Pryor not only knew his vulnerability before, during, and after his years of peak popularity, he was candid about it to a degree that was and is, I contend, unique among celebrities. The aspect of his honesty that most interests me relates to Pryor’s disabilities, especially those stemming from his MS diagnosis in 1986. I summarize the bare essentials here.

Onstage, Pryor performed his ambivalence about many difficult aspects of his life, including his struggles to maintain mental health (offering stories of his many “crazy” and depressed moments), his battles with addictions (to recreational drugs and to sex), and his fragile physical health (heart attacks, near fatal burns). The ambivalence that emerged from Pryor’s narration of such experiences was the main source of his humor and audiences almost always responded positively, not just with laughter but also with respect.

When MS and its symptoms were his performing topic, however, Pryor did not find the same acceptance and acclaim that greeted his earlier efforts. To preserve his identity and iconic status as the greatest stand-up comedy performer, audiences tended toward two perspectives on Pryor’s years with MS. One view saw this as a time of tragedy, with Pryor visible but as a pitiable, even abject figure. The other view was based on not seeing Pryor – looking away from him and what he did during this period, which included television and movie acting, memoir writing, and interview participation in print and electronic media.

For me, making time to explore these and other themes charged with race, disability, diversity, media, and comedy in the United States has been one of the favorite and most rewarding activities of my journey through academia. Along with reading most of the scholarly and general literature on Pryor (an expanding, exciting body of work, but not without its frustrations and gaps, some of which I’ve alluded to here), viewing relatively obscure and disregarded Pryor performances on VHS and DVD, and listening to his sprawling, transformative archives of stand-up appearances in audio, I’ve had opportunities to interview Margot Kidder, who acted alongside Pryor in several movies, and to spend time with Rain Pryor, one of his daughters and a galvanic actor, singer, and comic whose life has been anything but easy.

The results of all this are captured in hundreds of pages of my writing, the best of which will see publication in print soon. In the meantime, I find great fulfillment in sharing my work on Pryor in progress in spaces like this blog, and with peers at gatherings like the Disability Studies Seminar here at KU’s Hall Center for the Humanities. The diversity of backgrounds and interests represented by presenters and audience members at the seminar, now in its third year, is an invaluable resource. Our university’s SPED department and the Beach Center on Disability have been especially helpful to us as co-directors, Professors Sherrie Tucker of American studies and John Derby of Visual Art. Knowing that graduate students and faculty from these crucial campus sites are part of our audiences, and on our rosters of presenters, is most encouraging. Through the seminar and similar efforts, such as the See-Saw Film Festival, I have expanded my network of professional colleagues dedicated to disability studies.

The implications for building a foundation on which a disability studies certificate or minor, and ultimately a program or department can be established, are positive and proliferating. Public intellectual work for the sustainability and strength of the academy, and for a socially just world – from a disability studies perspective, it can and should include our support for spaces and places wherever disability culture is affirmed intersectionally. The more we learn to listen and listen to learn at such performances, the more real the differences we make will be (Lipsitz, 1990).

The implications for building a foundation on which a disability studies certificate or minor, and ultimately a program or department can be established, are positive and proliferating. Public intellectual work for the sustainability and strength of the academy, and for a socially just world – from a disability studies perspective, it can and should include our support for spaces and places wherever disability culture is affirmed intersectionally. The more we learn to listen and listen to learn at such performances, the more real the differences we make will be (Lipsitz, 1990).

Edited by Sorcha Hyland.

References

Cooper, E. (2007). Is it something he said: The mass consumption of Richard Pryor’s culturally intimate humor. The Communication Review, 10(3), 223-247.

Hall, J. D. (2005). The long civil rights movement and the political uses of the past. The Journal of American History, 91(4), 1233-1263.

Lipsitz, G. (1990). Listening to learn and learning to Listen: Popular Culture, Cultural Theory, and American Studies. American Quarterly, 42(4), 615-636.

Bio