Finding Hope

On November 9, 2016, we all woke up to a different reality than we might have imagined the morning before the presidential election. I was asked to write this blog post prior to the election and to explore what the new presidential administration would mean for special education and disability. At the time I was asked to write, I began to plan and outline what I would say. After the election, I took a long time to return to writing this blog because, honestly, I have no idea what the new presidential administration will mean for special education and disability. Let’s just get that right out there up front. I have no earthly idea what kind of impact this next presidential administration and Congress could have on special education and disability law in our country.

Sure, I could wax eloquent for a few paragraphs on the impact that school vouchers could have on students with disabilities. I could write an obituary for the Office for Civil Rights and what that could mean for enforcement of special education and disability law. But the truth is, those of us in the special education community have already discussed these things ad nauseam with each other and with our poor significant others and friends who are not in the special education community. None of us really know what the next four years will bring to special education and disability law and policy. Often I feel like the best thing for special education and disability law and policy would be for the next presidential administration and Congress to leave it alone. The status quo could be better than unknown changes. This may be hard to believe, especially after the way I have started this blog post, but I actually have a lot of hope for special education and disability law and policy over the next four years. I have hope because of two things: potential change we may see from the U.S. Supreme Court and our ability to effect change at the state and local level.

For those of you who have followed the U.S. Supreme Court this term you already know that this is an incredibly exciting time in special education law. This past fall I told my special education law students this nearly every week. During the fall semester these students had the privilege of diving into court briefs from two special education cases before the U.S. Supreme Court – Fry v. Napoleon Community Schools and Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District. You may have heard Fry referred to as “the service dog case” or the case with “Wonder, the Goldendoodle.” Fry is actually not at all about whether a student has a right to be accompanied by a service dog at school, but whether the Frys should have exhausted their administrative remedies under the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) even though they are not bringing their lawsuit against their daughter’s former school district under the IDEA, but are instead bringing it under the Americans with the Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and they are seeking a remedy not available under IDEA.

As if discussing the exhaustion of administrative remedies under the IDEA is not enough fun for all special education policy geeks, the U.S. Supreme Court did us the favor of taking a second IDEA case this term. The Endrew case could arguably be the biggest IDEA-related case of our careers, for those of us who were not around when the Rowley case was decided. The question before the U.S. Supreme Court in Endrew is what level of educational benefit a student with a disability is entitled to receive through a free appropriate public education. When you read this blog post, I hope that you will be spending your days and evenings dissecting the oral arguments that took place on January 11, as I will be. The Court seemed dissatisfied with the language used by the 10th Circuit to describe the FAPE standard, “merely more than de minimis,” but did not seem impressed by much of the proposed language suggested by the parents’ attorney or the attorney representing the Solicitor General. We will all look forward to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in these cases and what they will mean for our work. I am very hopeful that the outcomes of these cases could have a very positive impact on special education and disability policy.

I am also hopeful about the impact that we could have on special education law and policy at the state and local levels. Many of us may be unsure about the impact we could have on federal special education and disability policy, but I think there is a real opportunity to have an impact here in Kansas. There are many new members of the Kansas Legislature, including many current and former educators. The special educators who work and learn atop Mount Oread have so much to offer the Kansas Legislature and the Kansas State Board of Education. I hope you all – students, faculty, alumni, and friends feel encouraged and empowered to take your ideas and your research to the Kansas Legislature and the Kansas State Board of Education to help make special education better here in our great state. Wherever you live and work you should also consider taking your knowledge and your expertise to your local school district and talk to them about your ideas for improving special education. We should all work harder in the next four years toward bridging the gap between research and practice.

As you look ahead over the next four years I encourage you all to feel as hopeful as I do. Follow the Fry and Endrew cases and think about what the outcome of each could mean for your work. Follow state and local education issues and actively seek out your state senator, representative, and state and local board of education members. Talk with them about how we can improve special education in our state. Let’s not sit back and see what will happen to special education and disability law and policy over the next four years. Let’s work to make a difference right where we are, right now.

Laura Jurgensen is an attorney with the Early Childhood, Special Education, and Title Services team at the Kansas State Department of Education and teaches Law and Special Education at the University of Kansas. Laura earned her J.D. at Washburn University School of Law and did her undergraduate work in elementary education at Pacific Union College in California. She is thrilled to have accidentally fallen into a career in special education law. When she is not reading cases and OSEP letters, she and her husband are chasing their two toddler boys and loving (nearly) every minute of it.

Paradigm Flipping: A Tribal Citizen Lawyer’s Perspective

Image courtesy of the Muscogee (Creek) Indian Nation website located here.

To begin the New Year, Hawk Hopes Blog had the honor of recording a live interview with University of Kansas 2016 Langston Hughes Visiting Professor, Sarah Deer. Deer has worked to end violence against women for over 20 years. She is currently a professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. Her scholarship focuses on the intersection of federal Indian law and victims’ rights. A citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma, Deer is a co-author of three textbooks on tribal law. She has received national recognition for her work on violence against Native women and was a primary consultant for Amnesty International’s Maze of Injustice campaign. Her latest book is “The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America.” She is the recipient of a 2014 MacArthur Fellowship and KU Law’s first Langston Hughes appointment. Click here to listen to the live recording with Hawk Hope Blog editors, Sorcha Hyland and Lara Mann.

Could you tell us a little about yourself, your work, and your relationship to the University of Kansas (KU)?

DEER: I am a professor of law at Mitchell Hamlin school of law in Minnesota. I’m a citizen of the Muscogee Creek Nation of Oklahoma and I’m a graduate of KU two times over. I have my bachelor’s degree from KU and also my law degree from KU. This semester I’ve been lucky enough to visit here as a Langston Hughes visiting professor.

How did you come to understand the idea of disability from a tribal perspective?

DEER: I am framing this as coming from the perspective of mental health. I did anthology a few years ago where a Native woman had contributed a chapter about being a victim of sexual assault. In the aftermath of that she developed what could be described as Dissociative Disorder –leaving her body when thinking about the trauma. From her perspective, that was something that could be perceived as a gift or a blessing as opposed to detriment or disability. It really flips the paradigm—something that is natural outgrowth of trauma is not treated as a disease but treated as a reaction to some sort of oppressive power. That made a big impact on me because I’ve dealt with mental health issues most of my life, so thinking about flipping the paradigm was very informative.

Curricula across public and higher educational sys-tems fail to fully acknowledge the cultures and languages of non-dominant populations. In special education, we see significant problems with disproportionality—Tribal citizen students, students of color and linguistic minority students are funneled into special education. From your perspective, what do we need to do to better inform how we prepare teachers and how we operate from K-12 to the academy?

DEER: I think education around the history of tribal governments is very important. Somebody teaching in the inner city of a big city might think, ‘tribal nations don’t have any influence or impact on me’ but if you have Native students, or if you don’t have Native students, understanding the historical context of what has happened on this continent will prepare people to really be more critical about how they think about Anglo-American norms and values.

I’ve looked at how traditional family law may have worked. Often times the parents’ cultural protocol for dealing with a concern about that child was to refer to one of the grandparents. Let’s say Johnny’s not doing his math homework. The teacher tells the parents. The parents may need to inform one of the grandparents, depending on the culture. Then that grandparent will give instructive information back to the biological parent, who then will engage with the teacher and/or the child. A lot of times with our Anglo-American model of education, we think, ‘the parent should be striving immediately! If I tell the parent there’s a problem with this child, why are they not engaged with me? They must not care.’ rather than understanding that would be inappropriate in that family context for the parent to be the initial responder. That’s something I noticed in the ways in which kinship circles work in tribal communities.

Considering the very high rates of sexual abuse that is a product of oppression in tribal communities and reservations—issues around gender, young girls and their sexuality, protecting young girls and responding to young girls who have been victimized—what role might teachers play in that context?

DEER: I think it’s a fine line because statistically most of the Native girls in your classroom will be victims of sexual assault. That’s just the numbers. So how do you reframe that? I think one of my concerns would be that you would be potentially paternalistic or materialistic about ‘oh these poor girls.’ That could take over this framework which is not an empowering place to be. Understanding the reality that a majority of Native women will be victims of sexual assault might play a role in what you develop in terms of curriculum. Whether you address issues such as sexual assault in the classroom, if it’s connected at all to what you teach, or whether that’s something you need to be aware of but not necessarily engage in as an outsider, is a fine line. Being aware of it is certainly required for whatever course of action you take. If you don’t know about it, then you’re not going to be able to think about ways that you could be helpful for that community.

What’s your advice to white/majority K-12 teachers in public schools who have little context for teaching students who identify as Native or are part of a tribe?

DEER: When you discuss any issues that relate to Native America, particularly for the younger students, be very thoughtful about activities. Just the other day, my friend’s daughter who is Alaska Native, had to dress up as a pilgrim for Thanksgiving. Her mother didn’t do anything about it because, ‘how many battles can I fight today?’ You want to share information about Native Americans in a way that child can grasp but being really thoughtful about what’s actually happening in the classroom is important.

I think becoming educated about the particular area where you reside—the land where the school is, what tribal people occupied that land—acknowledge that and share that with your students so they’re aware. That land where they now stand once belonged to an Indian tribe. Those things can be really valuable to students and they relate to that kind of thing.

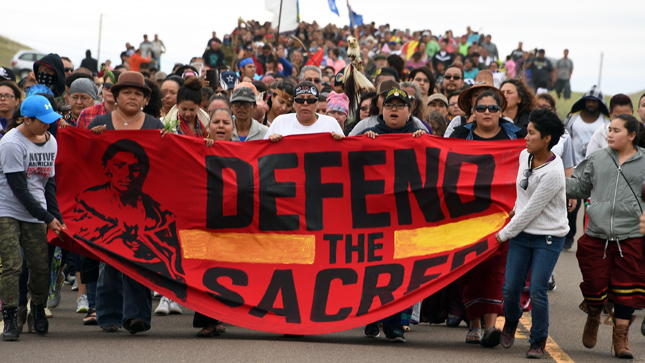

Tribal citizens at the Dakota Access Pipeline construction site near Cannonball, North Dakota. Photo by Arlo Iron Cloud from Indianz.com. Sourced here.

In what ways can teachers and educators incorporate the current pipeline protests and protectors into the curriculum so social transformation can be happening in the schools as well?

DEER: There is a professor of American Indian studies who uses her Indian name, Waziyatawin, also known as Angela Wilson, and she thinks children are often times quicker problem solvers than adults because they’re not constrained by their life experiences. She would explain to children how the Dakota people were divested of their land in the 1800s in a way that children could relate. She would ask ‘what should we do about that now? how should we resolve that? how can we make this right again? what could be fair?’ The kids would respond, ‘Native people to get their land back!’ and adults are really hesitant to say something like that. Engage in critical thinking, asking, ‘what is the pipeline?’ and then ‘what is an Indian tribe?’ Asking students to engage in critical thinking about how Indian tribes are affected by oil—how are all affected by oil—would be an innovative approach to middle school curriculum.

The Muscogee are traditionally matrilineal—how does this affect your work as a feminist?

DEER: It’s been very validating to do research about how traditional Muscogee people conceived of the world and gender and their epistemology—which was not pure equality in the sense that men were women and women or men—but that both genders and third and fourth genders had particular roles to play that were equally appreciated. That’s not to say that men did women’s work and women did men’s work; there was segregation, but the women’s work and role in the community was not denigrated and not discounted. I was thinking about reclaiming some of that heritage and engaging with tribal communities to think about ‘what does this mean for us today? how did patriarchy affect our tribe? how might we try to deflect patriarchy?’ is really exciting. There’s a lot of good information out there now about feminist approaches to tribal law and feminist approaches to indigenous studies.

How does the international world respond to your work and shape the way you approach it, in terms of frameworks, laws, and disabling environments that cause oppression?

DEER: What I learned working with Amnesty International is that the high rates of sexual violence can be framed as an international human rights crisis. That’s how it was framed in “Maze of Injustice.” I didn’t know what labeling would actually achieve but what it did achieve was changes in federal law. Senators were outraged when they read the report and they wanted to do something about it. That’s how we got the Tribal Law and Order Act and the Violence Against Women Act—Reauthorization through this understanding that the United States is a violator of human rights, and we can’t accept that. I’m not sure if the international human rights framework is resonating within individual tribal communities. Some tribes are engaged with the UN but I’m not sure it matters to every single tribe that we call it that. It’s more of this injustice, this oppression, some people call it an epidemic—which I pushed back on—but a crisis doesn’t necessarily need to have international language around it.

Riot police during prayer at the North Dakota Pipeline protest site. Photo by Rob Wilson Photography. Sourced here.

The image of a maze in “Maze of Injustice,” what epistemologies inform that idea that navigating your way to social justice involves going through this puzzling environment?

DEER: It refers to the legal system. It depends on if your victim is Native and your perpetrator is not, or you are non-Native and your perpetrator is Native, where did the crime happen, who is responsible, and what federal law applies to this reservation. The maze is the actual legal system itself.

How can a non-Native person borrow from a tribal framework that is not inherently their own? Is that potentially colonizing?

DEER: It can be. It’s a delicate issue for sure. I just finished an article on animal abuse in Indian Country and it’s a paradigm flip. The title of the article comes from a quote from a Native person; it’s called “Maybe the Animals Will Take Pity on Us.” It’s really saying that the traditional indigenous way of thinking about animals yields more productive outcomes when you’re thinking about our responsibilities to the animal world and the animal world having pity on us as humans because they’re so much wiser than we are.

As I was working on the article, I was reading a piece by a non-Native person who was saying, ‘let’s be thoughtful about how we engage with traditional ecological knowledge’ that can be useful and very helpful. But it’s our language, our knowledge, so we need to be given credit for it. There are certain parts of our traditional ecological knowledge that might not be appropriate for us to share with people who are not part of our community. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong answer to it, but it has to be a really thoughtful engagement, otherwise things can feel disrespectful.